...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Jacqueline Alio | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

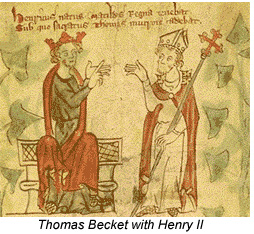

A few years after his schooling, Thomas started working as a clerk for Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury. According to biographies of the saint, it seems that in the beginning young Thomas had no vocation for the clergy. Appreciating his clerk's potential and good will, and having in mind his promotion, Archbishop Theobald sent Thomas first to Bologna and then to Auxerre so that he could study law. By this time, Thomas had finally found his calling for the Church, though this was not immediately obvious. Thanks to his acquaintance with Archbishop Theobald, Thomas Becket entered into the graces of King Henry I and of his son Henry II, eventually becoming the royal chancellor for the latter, and one of his closest friends. This friendship though was destined to bring ruin into the life of Becket. After having worked in the court of Henry II for a number of years, in 1162 Thomas was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest See of England, by the King, who in doing so, believed that he had a sure ally within the Church of England. Although up until his new appointment Thomas had always supported the King's decisions, as Archbishop of such an important See, Becket felt that his loyalties no longer lay with the King, but with God and the Church. The love affair between Sicily and Thomas Becket began a few years later when the Archbishop of Canterbury was forced to flee to France in self-imposed exile after not having accepted the Constitutions of Clarendon with which King Henry II placed himself as the supreme ruler of the Church of England - as judge not only of laymen but also of bishops and other clergy accused of crimes. Thus Becket's exile to France in 1164, but he was not alone: some of his friends and kinsmen also had to flee England and they found refuge at the court with King William II of Sicily and his mother Margaret of Navarre (there exists a letter of Becket thanking the young Sicilian king for this hospitality). Support also came from some of Becket's Anglo-Norman friends in Sicily such as Archbishop Richard Palmer. In the meantime, this connection between England and Sicily reached a climax around the year 1168 when King Henry II of England sought to betroth his youngest daughter Joan, who was only a toddler at the time, in marriage to William II of Sicily, who had not yet reached the age of majority.

At this point the marriage was called off, but a few years later, after Henry II performed public penance on Becket's tomb and the Archbishop was canonised in 1173, relations between the two houses picked up again and in 1177 Princess Joanna and King William II were finally married. Almost immediately after the canonization of Saint Thomas Becket, two important works were started in Sicily in honour of this much beloved saint. The mosaic representing Becket in the main apse of the Cathedral of Monreale near Palermo is the earliest know artistic representation of the saint anywhere in the world; the inscription reads simply "Saint Thomas of Canterbury." The Cathedral of Marsala, in western Sicily, is still dedicated to Saint Thomas of Canterbury despite having been restructured several times. Another fact regarding the saint's relics is of great interest. Many years after Henry VIII of England destroyed Thomas Becket's tomb and dispersed all his relics in 1538 during the Reformation of the Church of England, a few early relics of the saint were sent back to England from different places in Italy including Sicily. Some are preserved at the small Catholic church dedicated to Thomas in Canterbury itself. Thomas Becket is not the only link between the Norman kingdoms of England and Sicily. There were more connections between the Sicilian and English Normans during the twelfth century than most people realise. There had been an early link during the eleventh century with the marriage between the Great Count Roger I, the founder of the Norman dynasty in Sicily, and Judith of Evreux, his first wife: Judith was a cousin of England's William the Conqueror, but she died before giving an heir to Count Roger, who eventually married Adelaide of Savona, with whom he had his son and heir Roger II, the great and tolerant King of Sicily and of Southern Italy.

It should not be forgotten that Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror, died in Palermo in 1097 during a visit with Roger I en route to the First Crusade. Richard Lionheart passed through Sicily about a century later on his way to a later Crusade. All this proves to us how common it was for the Normans in both kingdoms to move from one court to the other and that the often undocumented ties between the dynasties are far more vast than we may ever know. About the Author: Historian Jacqueline Alio wrote Women of Sicily - Saints, Queens & Rebels and co-authored The Peoples of Sicily - A Multicultural Legacy. | ||

Top of Page |

Saint

Thomas Becket was born in 1120 into a predominantly Norman, but

non-aristocratic, family of London. His father Gilbert was a prosperous

merchant, and he sent his son to various schools in England and also to

a school in Paris, which was a common practice at the time for English boys

trying to move up the social ladder.

Saint

Thomas Becket was born in 1120 into a predominantly Norman, but

non-aristocratic, family of London. His father Gilbert was a prosperous

merchant, and he sent his son to various schools in England and also to

a school in Paris, which was a common practice at the time for English boys

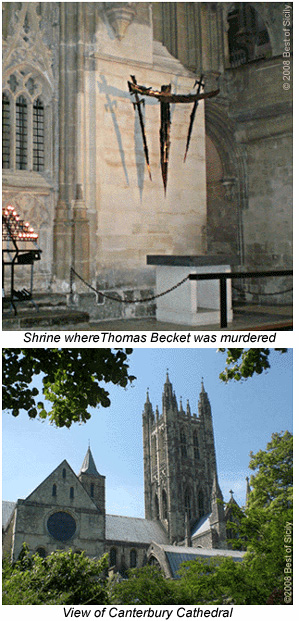

trying to move up the social ladder. The King of England hoped in this way to strengthen the ties between

the two Norman houses. A few English Normans living in Sicily, including

Archbishop Palmer, were even negotiating with Pope Alexander III to smooth

the path for an English marriage in Sicily, but before the marriage contract

was approved, a terrible scandal broke out in England. Archbishop Thomas

Becket, who had just returned to England in the hope of a reconciliation

with King Henry, was murdered in Canterbury Cathedral on December 29, 1170.

Four of Henry's knights were responsible for Becket's death, although when

questioned they claimed that they were only following the king's request

to be rid of a "meddlesome priest."

The King of England hoped in this way to strengthen the ties between

the two Norman houses. A few English Normans living in Sicily, including

Archbishop Palmer, were even negotiating with Pope Alexander III to smooth

the path for an English marriage in Sicily, but before the marriage contract

was approved, a terrible scandal broke out in England. Archbishop Thomas

Becket, who had just returned to England in the hope of a reconciliation

with King Henry, was murdered in Canterbury Cathedral on December 29, 1170.

Four of Henry's knights were responsible for Becket's death, although when

questioned they claimed that they were only following the king's request

to be rid of a "meddlesome priest." Of

course there were also other connections which had to do with clergy,

clerks, administrators and bookkeepers from either the English or Sicilian

Norman Kingdoms working in one kingdom and sometimes travelling to visit

or actually moving to work in the other one. A few names that come up are

Richard Palmer, Archbishop of Siracusa in Sicily, Hubert of Middlesex, Archbishop

of Conza near Naples, and Thomas Brown, who was first a clerk to the King

of Sicily and later treasurer to the King of England, and who apparently

introduced Arabic numerals (and perhaps even certain principles of

Of

course there were also other connections which had to do with clergy,

clerks, administrators and bookkeepers from either the English or Sicilian

Norman Kingdoms working in one kingdom and sometimes travelling to visit

or actually moving to work in the other one. A few names that come up are

Richard Palmer, Archbishop of Siracusa in Sicily, Hubert of Middlesex, Archbishop

of Conza near Naples, and Thomas Brown, who was first a clerk to the King

of Sicily and later treasurer to the King of England, and who apparently

introduced Arabic numerals (and perhaps even certain principles of