...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Luigi Mendola | ||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

So one reads in Roger Peyrefitte's Knights of Malta published in English to critical acclaim in 1959. The knightly orders historically associated with Sicily and Sicilians are, if anything, even more arcane. One of them is the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George. Unlike the Order of Saint John (now the Order of Malta), this institution was founded after the Middle Ages. Like the Order of Malta, it was engaged during the sixteenth century in the defence of Europe from the Turks. The difference is that while the Knights of Malta were involved primarily in sea battles, the Constantinian knights fought on land in the Balkans.

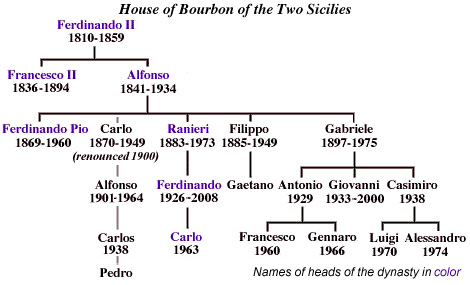

In its earliest years, the Constantinian Order constituted a small fighting force under a dynasty of Byzantine exiles in Venice who claimed the Crown of Constantinople - hence the order's name and Eastern tradition. Whether these pretenders enjoyed the most legitimate claim to the Byzantine Throne and its distinguished Comnenus dynasty is a matter of scholarly debate, but the Counter-Reformation Papacy - never having forgotten the effects of the Great Schism of 1054 or the Christians' loss of Constantinople in 1453 - supported their position. In 1555 Pope Julius III recognised both the order and the dynastic claim of the Angelus and Drivastus pretenders who had aided the cause of Scanderbeg and the Albanians. In 1697 the last heirs of this dynasty ceded the grand magistracy of the order to Francesco Farnese, Duke of Parma. By this time the order itself no longer had an explicitly military purpose, though its ranks included many military men. It had, in fact, become one of the more subtle instruments of the Counter Reformation, and to this day a number of cardinals and bishops, including those of Naples and Palermo, are ecclesiastical knights. In 1727 the last male Farnese, Antonio, ceded the order to the eldest son of Elizabeth Farnese, second wife of King Philip V of Spain. When Carlo (Charles) de Bourbon (Elizabeth's son by Philip) came to Italy to claim his rights as Duke of Parma and King of both Naples and Sicily, the Constantinian Order formed part of his inheritance from the Farnese dynasty. Beginning in 1734, the Constantinian Order of Saint George, as an important dynastic order of the Sicilian dynasty, enjoyed great prestige in Sicily. (Only in the nineteenth century were the crowns of Naples and Sicily united to form the "Two Sicilies" officially, though the name traces its origin to the time of the Vespers uprising in 1282.) Palermo's medieval Basilica of the Magione, once a conventual church of the Teutonic Order, became the Constantinian Order's ecclesiastical seat in Sicily in 1787 and remained so until the 1860s when Sicily was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy. For around 125 years the Constantinian Order was one of the most important aristocratic institutions in Sicily. In 1759 King Carlo abdicated his Italian rights in favour of his young son, Ferdinando, to ascend the Spanish Throne as Carlos III. From afar, he stayed in contact with Ferdinando and the young monarch's mentors, and continued to take a hand in the administration of the Constantinian Order, but he had forever separated the crowns of Spain and Sicily to ensure that no single sovereign could ever rule both kingdoms. (As recently as 1900, four decades after the loss of the Two Sicilies, one of his descendants who stood in line to inherit headship of both houses renounced his rights to the Sicilian Crown and his descendants are today part of the Royal House of Spain.) The order was transmitted with the Crown from father to son through Ferdinando I, Francesco I, Ferdinando II and then to Francis II. It was, and remains, a Roman Catholic institution, although its founders were Orthodox Christians.

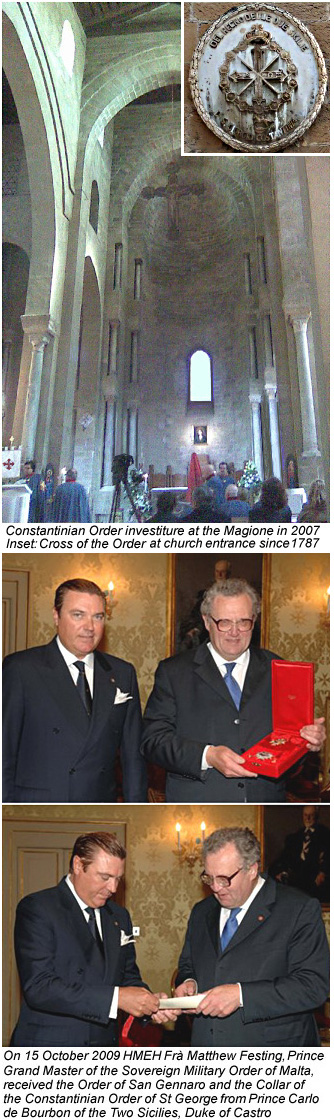

The peculiarities of international law which permit institutions such as the orders of knighthood of non-reigning royal dynasties to flourish would take volumes to describe in detail. The point is that a few rights and prerogatives are maintained long after a sovereign is deposed, and some of these are transmitted to his heirs. What is interesting is that while Italy, like most other republics in Europe, does not recognize titles of nobility- whose social use is not actually outlawed - it does recognise several dynastic orders which in the past were closely associated with the aristocracy. In addition to the Constantinian Order, the Head of the House of the Two Sicilies is grand master of the Order of San Gennaro (St Januarius) and the Order of Francis I, which may be bestowed upon non-Catholics. Considering the island's history, Sicily is not such a strange place for the knightly orders to survive. Churches, castles and commanderies once associated with the medieval Hospitallers, Templars and Teutonic Knights dot the landscape. The heart of Saint Louis - perhaps the ultimate crusading knight - is preserved at Monreale Abbey overlooking Palermo. The idea of knightly investitures being held in such places is in keeping with centuries-old tradition, and Carlo de Bourbon, the man who would be king, is a descendant of Sicily's medieval Norman, Swabian, Angevin and Aragonese monarchs. In addition to philanthropic work undertaken without fanfare, the Constantinian Order is a point of reference for the historical heritage of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Like the dynasty to which it belongs by hereditary right, it has close historical ties to the Sovereign Military of Malta. Malta and Gozo were a fief of the Kings of Sicily until the islands were seized by Napoleon in 1798 en route to Egypt and the knights expelled; they found refuge at Catania and Messina before establishing themselves in Rome. The Grand Master of the Order of Malta, Frà Matthew Festing, like his predecessors, is a Constantinian knight. It is not unusual for southern Italian knights and dames of Malta to be associated with the Siculo-Neapolitan order as well. The year 2008 saw changes in the grand magistral leadership of both institutions, with Carlo de Bourbon succeeding his late father, Ferdinando, as Duke of Castro and Head of the House of the Two Sicilies (and therefore grand master of its orders) while Matthew Festing was elected following the death of Andrew Bertie, the fellow Englishman who ably led the Order of Malta for two decades. The Italian government has recognised the order for many years (several former prime ministers are Constantinian knights) and permits its decorations to be worn on military uniform and by Italian diplomats. A number of high-ranking officers of the Italian armed forces and Carabinieri are Constantinian knights. Here an important point should be clarified. Italy recognizes a few of the orders of the dynasties that ruled the pre-unitary Italian states before 1860 as a question of national heritage and history. However, the dynastic heads who award these orders have no special privilege; if they are addressed as Your Highness it is merely by courtesy. The hereditary, vestigial trappings of these monarchies - titles of nobility and coats of arms - are not recognized (or protected) though their private use is permitted as a form of freedom of expression. The order, which numbers several thousand knights and dames around the world, again uses the splendid Magione - now a parish church - for its occasional ceremonies, and does much to assist the poor of Palermo and other parts of Sicily. Its ranks are not exclusively aristocratic but its traditions certainly are. The Constantinian Order may be bestowed for merit, but it is primarily a "military-religious" chivalric order in the tradition of those founded in the Holy Land during the Middle Ages. Today, most of the knights and dames in the Order of Malta, the Order of the Holy Sepulchre and the Constantinian Order of Saint George are not aristocrats by birth but rather devout Catholics, from all walks of life, who support works of charity in Italy and around the world. The sword has given way to the helping hand. The Savoys, who ousted the Bourbons in 1860, ruled Sicily for over eighty years, and a few Sicilians born late in the Bourbon era actually lived to see the Savoys deposed by referendum in 1946. There is little point in demonising one dynasty or glorifying the other, but it is clear that Sicily had a stronger identity under the Bourbons than it had under the Savoys. The Constantinian Order is one small, living piece of that legacy. About the Author: Luigi Mendola has written about heraldry and related topics. | |

Top of Page |

"Men

from a single social and even religious caste formed into an order whose very existence is not suspected by the man in the street."

"Men

from a single social and even religious caste formed into an order whose very existence is not suspected by the man in the street." Both the order's symbolism - the Chi Rho monogram of Christ with

the motto In Hoc Signo Vinces - and its legend were inspired by Emperor

Constantine's victory at Rome's Milvian Bridge during the fourth century. In fact, the order was founded a few decades after

the fall of his capital, Constantinople, to the Turks some ten centuries later (in 1453).

Both the order's symbolism - the Chi Rho monogram of Christ with

the motto In Hoc Signo Vinces - and its legend were inspired by Emperor

Constantine's victory at Rome's Milvian Bridge during the fourth century. In fact, the order was founded a few decades after

the fall of his capital, Constantinople, to the Turks some ten centuries later (in 1453). The last King of the Two Sicilies,

The last King of the Two Sicilies,