...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Luigi Mendola | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

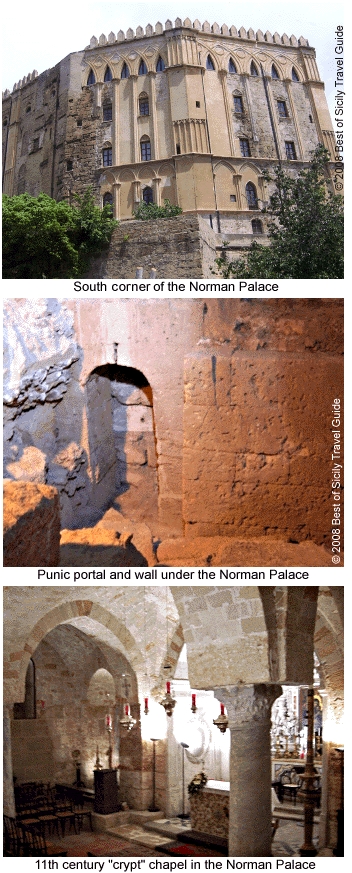

Origins To the Greeks the port city was an irritating reminder of Carthaginian power in western Sicily and a springboard for Punic attacks on Greek cities such as Himera to the east. Zis, of course, was not the only such annoyance; there were also Motya and Kfra (or Solus or Soluntum), the latter of which fell to Greek power in 396 BC. Following the fall of Greek Sicily to Rome, the rulers of the emerging Empire simply couldn't tolerate a competing power in the central and western Mediterranean, hence the Punic Wars, with Punic Palermo as one of their main battlegrounds. The Romans had, in a sense, inherited the Greeks' complex power struggle against the Carthaginians. Carthage fell, followed by Rome. The Vandals and Goths discovered Panormus but didn't stay long. For the Byzantine Greeks Palermo, and therefore the high point of the city built around what is now the Norman Palace, never warranted so much attention as Syracuse on the Ionian coast. In the meantime the shoreline receded and the population dwindled, to be restored by the Arabs in the ninth century. They build the emir's large citadel, al Kasr, over the walls of the Carthaginians' fortress overlooking the Kemonia River nearby, and expanded their new metropolis in every direction, erecting administrative buildings in the district claimed from the sea, al Khalesa (today's Kalsa). Until the unification of Italy in 1861, the street now called "Corso Vittorio Emanuele" (for the new monarch) was, in fact, called "Via Cassaro." This district, like the Kalsa, was known by the Italianised version of its Arabic name. Sicily's Aghlabid emirs (a Tunisian dynasty) ruled by authority of the Fatimids, their suzerains until 948. Under the Aghlabids' successors, the local Khalbids, the unified Emirate of Sicily, such as it was, divided several times, though Bal'harm (Palermo) remained the island's nominal capital and most important city. The cooperation of rival emirs with the invading Normans rendered a difficult conquest less difficult. With the arrival, in 1071, of Robert Guiscard and his younger brother, Roger, the stage was set for Palermo to assume its rightful place as a European capital. Al Kasr became the fortress of Palermo's - and Sicily's - rulers. It was restructured around four large towers: the Pisan, Greek, Kirimbi and Joaria.

From outside the visitors' entrance, a few pointed battlements have been preserved, but most of these crenels are relatively recent modifications. Originally there were battlements in some parts of the palace. Most of its medieval walls, both inside and out, are now obscured by the less attractive additions of subsequent times, but the Pisan Tower of the Normans' Royal Palace looks much as it did nine centuries ago, at least from the outside. Don't judge it from outside, for if its exterior is less than impressive, the palace's interior still evokes much of its former grandeur. The Royal Palace now houses the Sicilian Regional Assembly,the parliament of Italy's largest semi-autonomous "regional" government. Roger II ordered the palace's enlargement sometime before 1132, though the existing structure already included the simple chapel (now the "crypt") near ground level. It was actually a castle in the most traditional sense, complete with a garrison (the royal bodyguard), victual stores and armory - though with a lavishness of design rare in western Europe in the twelfth century. The Palatine Chapel Recently restored, the ceiling has some interesting images, and even Arabic script. Lions and eagles are prominent. One of the more remarkable images shows chess being played - an indication of the intellectual pursuits of the medieval Palermitans. Dancing is also depicted. Islamic practice generally discouraged the artistic representation of humans in portraiture, but these paintings in tempera, part of what is widely considered the largest single Fatimid work of art of its day, seems to reflect the relaxed norms of a tolerant society. Though the architectural construction of the chapel was probably completed by 1140, the artistic phase certainly required several more years. The ceiling is the work of local and Tunisian artists. The mosaics - many representing Biblical scenes - were created by Orthodox monks from Sicily, mainland Italy and Greece (and as far away as Constantinople), the same artists who worked on the Martorana. The stone inlay of the floor and lower walls is also a very demanding craft requiring much skill and effort. The Old Testament scenes of the nave walls (there are none from the New Testament although apostles and angels are represented on other walls) offered the advantage of appealing to Christian, Jew and Muslim alike. On the wall behind the throne platform is the coat of arms of Aragon added some time after the Sicilian Vespers war of 1282 when that dynasty began its reign in Sicily. The mosaics outside the chapel are modern additions. It is not known whether the Hautevilles ever used as their coat of arms a red and white checkered bend on a blue field. Roger's Salon Astronomical Observatory Crypt Chapel and Donjon Punic Wall About the Author: One of Sicily's foremost historians, Luigi Mendola is the author of two books. | ||

Top of Page |

It looks medieval, with a generous dose of the Baroque added

over the centuries (and by 1400 the imposing

It looks medieval, with a generous dose of the Baroque added

over the centuries (and by 1400 the imposing  View from the palace

View from the palace