...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Roberta Gangi | ||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily |

It's a Sicilian thing. Like other typically Sicilian crops, fava beans (scientifically known as vicia faba) were introduced on the island in the remote past, perhaps by the Phoenicians, Greeks or Romans, if not much earlier. Nobody really knows for certain. It is thought that, like lentils and chickpeas, they became part of eastern Mediterranean cuisine during the neolithic agricultural era, certainly by 6,000 BC (BCE). Fava beans are apparently native to south-western Asia, from India to the Arabian peninsula and Asia Minor, and cultivation spread along Africa's Mediterranean coast - and then to Sicily - in the distant past. Fresh, chopped fava beans are one of the main ingredients of falafels. Favas are part of many Asian and African cuisines. In Egypt the spread known as ful-medames, consisting of mashed, boiled favas, olive oil, garlic and lemon juice has been very popular for centuries. In Sicily the fava, harvested beginning in the middle of March, is used, along with fresh green wild artichokes and peas, to make fritella. Another popular dish is the soup known as macco or maccu, which can be made either with fresh (green) fava in springtime or from dried (tannish colour) beans in autumn and winter. Macco contains little more than crushed fava beans and olive oil seasoned with a touch of onion, salt and pepper. In fact, the natural flavour of the beans is so strong that recipes calling

for fava rarely contain too many competing ingredients. While fresh fava

beans can be eaten raw, cooking brings out their distinctive flavour. Creative recipes abound. Try mixing partially mashed, boiled fava into a fritatta (omelette) made with Italian grated cheese. Boiled fava added to garlic sautéed in a good olive oil makes a great pasta condiment or a spread on crackers or bread. Fava beans are full of natural fiber and they're a good source of many vitamins and minerals. This includes L-dopa, and in recent years fava beans have been recommended for those suffering from Parkinson's Disease. The beans are high in tyramine. The food allergy associated with fava beans, appropriately called favism, occurs with some frequency in Mediterranean populations affected by anaemic disorders (which evolved as a genetic response to malaria). Haemolytic anemia can result in those having this life-threatening allergy, and in some cases a reaction develops even if they merely inhale pollen from fava blossoms. More precisely, favism results from glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, an X-linked recessive hereditary enzyme deficiency somewhat more frequent in children and men than in women. The condition is very rare and, in most cases, usually present without symptoms. When boiling fresh fava, drain the water (which may turn dark) after four or five minutes, rinse the beans and then continue boiling in fresh water for five minutes more (or until they're tender or the skins loosen). For some recipes - such as spreads and pasta sauces - you may wish to remove the skins after boiling. Fresh is best, and fava are cultivated throughout the Americas and much of the world, though harvest seasons vary. In some markets they're sold in cans or jars or even dried. In any recipe requiring olive oil, always use the best extra-virgin olive oil you can find. About the Author: Roberta Gangi has written numerous articles and one book dealing with Italian cultural and culinary history, and a number of food and wine articles for Best of Sicily Magazine. | |

Top of Page |

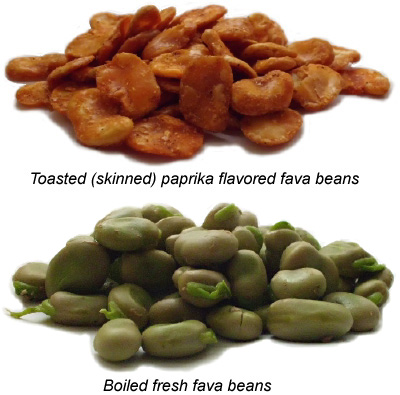

Picture this. You're at a bar in Sicily

where you order bitters, champagne or one of those other drinks they serve

with "munchies" like olives, peanuts or potato crisps. One of the enticing

snacks looks a little like reddish barbecued potato chips, only thicker

and a bit smaller. Salty and spicy, they have a robust flavour but at first you can't

quite figure out what they are. Then it dawns on you. You're eating toasted

fava beans (broad beans) flavoured with paprika.

Picture this. You're at a bar in Sicily

where you order bitters, champagne or one of those other drinks they serve

with "munchies" like olives, peanuts or potato crisps. One of the enticing

snacks looks a little like reddish barbecued potato chips, only thicker

and a bit smaller. Salty and spicy, they have a robust flavour but at first you can't

quite figure out what they are. Then it dawns on you. You're eating toasted

fava beans (broad beans) flavoured with paprika.