...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Carlo Trabia | ||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily |

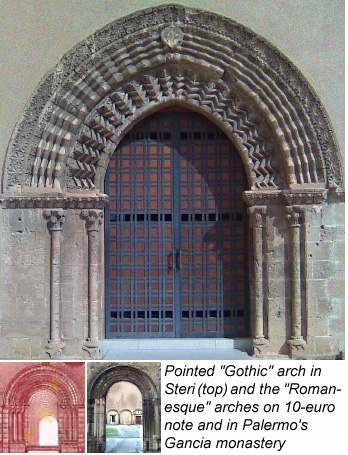

It's difficult to separate the early Gothic from the Romanesque - the arched two-light window is claimed by both movements. What eventually evolved in Sicily and much of Italy was a hybrid, the so-called Romanesque Gothic. Pointed arches, rose windows and Gothic decoration were part of this. High, thin walls, large stained-glass windows, gargoyles and majestic bell towers were not. While the Gothic became strongly identified with Normandy, it was unknown to the Normans who conquered Sicily and England in the eleventh century. In their earliest form, the cathedrals of Canterbury and Westminster were Romanesque. Each style has its devotees who, most typically, abhor the Baroque style spawned by the Renaissance. Contrary to popular belief, Romanesque arches - portals, windows, vaults - were often pointed. In the case of portals (doorways), the Gothic and Romanesque designs originating late in the twelfth century were virtually identical. By around 1250, the only subtle difference between the two styles of arch might be that the Gothic one was pointed while the Romanesque one was not. Subtle indeed. One effect of such reasoning is that the arched portals of the Steri Palace (shown here) are regarded as a "Gothic" form while those of the Gancia monastery around the corner (and the similar one depicted on the 10-euro note) are usually described as "Romanesque."

Faux columns, a decorative keystone and a few acanthus leaves or other detailing rendered each arch unique. All kinds of moulding ornamentation were used: the zig-zag "dog tooth" motif (a variation is shown here) was commonplace, and so was various geometry and foliage. In Sicily it was common practice to use alternating colours of stone along the archivolt, thus creating an interesting visual effect without altering the cut or shape of the stones. The example shown is the entrance to the Hall of Barons in the Steri Castle. The raftered ceiling of this large chamber, resplendent with coats of arms and various paintings from the fourteenth century, has been preserved almost in its original form. The shield atop this arch, sculpted in relief on the keystone, once bore the coat of arms of the Chiaramonte family who erected the fortified palace. The heraldic shield was defaced following the family's fall from grace. The keystones of the portals of churches and monasteries often bear decorations such as a stylised cross or the Paschal Lamb; heraldry is more common in the entrances to castles and palaces. In Sicily the medieval arched portals represent a very special architectural link to the rest of Western Europe. It's amazing, considering the wholesale redesign of medieval churches with the advent of the Baroque, that so many survive. In fact, some were hidden by stucco or (in the case of the arched gate in Gela) dismantled, to be restored to their original glory only in the twentieth century. We should rejoice at their return. About the Author: Carlo Trabia is an architect who lectures on architectural history. | |

Top of Page |

The churches and palaces of

Sicily and

The churches and palaces of

Sicily and