...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Luigi Mendola | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

In this mix loyalties were often fickle and internecine quarrels were not unheard of. One Byzantine Greek military commander might fight another, while one emir may view another as a rival. In 1054 Schism divided the Christians, and by 1095 some zealous European Christians were raising armies for a full-scale invasion of Palestine. This was the world of George Maniakes, a distinguished general in the service of the Byzantine emperor Michael IV. Little is known of his early life, but by 1030 Maniakes was fighting the Muslims at Aleppo in what is now northern Syria. The next year he went on to capture Edessa, to the east in upper Mesopotamia, from the Seljuk Turks. A Norse force led by Harald Hardrada, who would later become King of Norway, formed his Varangian Guard. With some Normans under the command of William, a brother of Robert and Roger of Hauteville, and a Lombard contingent from Italy, Maniakes launched a series of assaults on Sicily, which was then under Arab control. From 1038 until 1040, Maniakes' diverse group of mercenaries defeated Arab forces in south-eastern Sicily. Here the jewel in the crown was the city of Syracuse. Though surpassed by Bal'harm (Palermo) in wealth and importance, Syracuse was still a gateway to the East. It was in Sicily that the knight William Hauteville earned his nickname, "Iron Arm," by killing the emir of Syracuse with a sword in single combat. For now, George Maniakes was satisfied to conquer Syracuse, controlling it from the coastal fortress on the island of Ortygia that still bears his name, but though he was appointed catapan of Italy his victory was to be ephemeral.

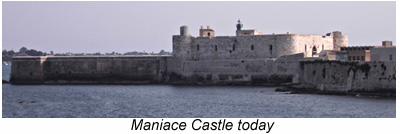

This made it difficult for Maniakes to hold his piece of Sicily. Maniakes likewise offended Stephen, his admiral, who had important connections back in Constantinople. Clearly, Maniakes was no paragon of tact and no master of politics. In Maniakes' absence, the crown had passed to the opportunistic Constantine IX, who failed to appreciate the general's accomplishments in Sicily. The general was recalled to the capital in 1042 and Syracuse once again fell into Arab hands. Adding insult to injury, when Michael Doukejanos was appointed catapan of Italy, replacing Maniakes, he gave Arduin the city of Melfi as a fief. More importantly to posterity, their service to Maniakes convinced the Normans that Sicily was indeed within their reach, and that its emirs were far from invincible. The Hautevilles would return to Syracuse in 1085, led by William's younger brother Roger. In the end, it was a personal feud that led to Maniakes' fall from grace. A certain Romanos Scleros, like Maniakes, was a wealthy landholder in Asia Minor and the two had fought over land. It was said that Scleros urged his beautiful, lusty sister to influence the emperor Constantine to act against George Maniakes. This was typical of the blunders and intrigues that would cost the Byzantines an empire. Scleros ransacked Maniakes' home. The avaricious Scleros demanded that Maniakes concede him control of Apulia. Maniakes killed Scleros and, having been declared emperor by his loyal troops, including the remaining Norsemen, attempted to take Constantinople. He was killed at the ensuing Battle of Thessalonika in 1043. At this distance of time, it is difficult to form a clear portrait of George Maniakes. Seen in his best light, he was a capable, visionary military leader who was not appreciated in his own country. Maniace Castle stands on a site that was already fortified by the Arabs before Maniakes arrived. Greatly expanded by Frederick II, the fortress we see today is essentially a thirteenth century structure. Peter of Aragon used this as one of his bases during the Vespers War. In the nineteenth century Lord Nelson was given the seaside castle (and the town of Bronte) as a personal fief; his heirs sold it to the city of Syracuse in the 1980s. About the Author: Historian Luigi Mendola has written for various publications, including this one. | ||

Top of Page |

The Mediterranean world of the eleventh

century was a complicated place, with several ambitious powers vying for

territory. In the East the

The Mediterranean world of the eleventh

century was a complicated place, with several ambitious powers vying for

territory. In the East the  The chroniclers

tell us that Maniakes publicly insulted Arduin, the Lombard leader, who

decided to withdraw back to peninsular Italy. William and the Normans decided

to follow the Lombards - even though back in Apulia the two were not always

on the most amicable terms with each other or with the Byzantines. Worse,

Harold and most of the Norsemen also abandoned Maniakes.

The chroniclers

tell us that Maniakes publicly insulted Arduin, the Lombard leader, who

decided to withdraw back to peninsular Italy. William and the Normans decided

to follow the Lombards - even though back in Apulia the two were not always

on the most amicable terms with each other or with the Byzantines. Worse,

Harold and most of the Norsemen also abandoned Maniakes.