...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Michele Parisi | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

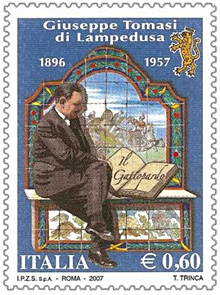

Published in Italy in 1958 following its author's death, The Leopard soared to the summit of international bestseller lists in 1961. The author, a Sicilian nobleman, weaves a fabulously rich tapestry of Sicilian aristocratic life around 1860, when the Risorgimento (unification movement) interrupts more than a century of Bourbon rule by the Kings of Naples. As the Kingdom of Naples (or the Two Sicilies) comes to an end, a new order arrives, but is it nothing more than the old order in new clothes? Drawing upon his own very special family history and experience, the Prince of Lampedusa evokes in the reader's mind the image of a unique moment in Sicilian history with the skill of a master storyteller, notwithstanding that this was his first lengthy piece of work. The Leopard, it has been suggested, took a lifetime of contemplation to write. It is the story of great change seen through the eyes of a middle-aged Sicilian prince not unlike the author. The story revolves around the experiences and dilemmas of Fabrizio, Prince of Salina, owner of numerous large estates in the Sicilian heartland. He owes his nickname, "the Leopard" (il Gattopardo), to the proud beast depicted in his coat of arms. As a member of the ancien regime at the time of Garibaldi's landings, Fabrizio must decide how - and whether - to embrace the new monarchy about to supplant the old one. At the same time, he must navigate through a sea of new economic challenges posed by an emerging class of bureaucrats, social climbers and rustic entrepreneurs, one of whom is the wealthy but poorly-bred father of the beautiful woman that his nephew (and ward) wants to marry. It is abundantly obvious that this love affair is not without complexities of its own. Subplots focus on the romantic interests of the prince's daughters and even the marriage of the niece of the family chaplain, a Jesuit. The role of the Church is not overlooked. Complex relationships and connections abound. Implications await just beyond view, around every baroque corner, poised to devour the reader's suppositions about life in nineteenth-century Sicily. The novel reflects astounding insight into Sicilian attitudes about the Risorgimento, particularly (but not exclusively) from the point of view of the nobility. The implicit analogy between the events of 1860 and those of 1943 is never far away. The author witnessed the latter, and he began work on his manuscript amidst the rubble of post-war Palermo. Through the novel's characters, Tomasi was one of the first, but certainly not the last, in Italy to state openly that the referendum of 1861, ostensibly giving the new regime a statistically improbable 98% of the vote, was obviously rigged. Until Sicily was liberated in 1943, the Fascists might have imprisoned anybody who even suggested such a thing. When The Leopard hit the English language market, the Times Literary Supplement called it "a masterpiece." It became a classic almost overnight, helped along by the mystique of the reclusive author whose sequel, The Blind Kittens, remained unfinished at the time of his death. Fathers and Sons and Gone With the Wind have expressed the same magical aristocratic spirit of the 1860s, though in very different contexts. The novel really is not reactionary. It isn't even very flattering of one dynasty at the expense of the other. Following eight troublesome decades of Savoy rule that culminated in the Second World War (which left the real-life prince's family palace a pile of stone), The Leopard challenged a number of classroom clichés about the unification movement and Garibaldi's invasion of Sicily. It was one of the first works of fiction to do so. Historical fiction usually presupposes at least some knowledge of history on the part of the reader. So thoroughly had Sicily's pre-1860 history been whitewashed and revised since the 1860s, it was necessary for literary critics, journalists and historians to remind Italians - and even Sicilians - what it was and even which dynasty ruled Sicily immediately before the Savoys. The English edition was ably translated by Archibald Colquhoun, and in some printings his lengthy translator's note is included. Luchino Visconti made the story into a film starring Burt Lancaster and Claudia Cardinale. The true Sicilian aristocracy was a dying caste during Tomasi di Lampedusa's lifetime. It's all but extinct today. This remarkable novel, with its fascinating themes and "unconventional" views, gives us an idea of what the Sicilian nobility was. There was meant to be a sequel. The first chapter of the incomplete second novel, The Blind Kittens, was eventually published, featuring, again, the family described in The Leopard, but portrayed from the point of view of the new wealthy class. Judging from the solitary chapter completed, it is a tale that would not have disappointed readers, while the short story The Professor and the Mermaid also features a descendant of the prince. Dripping social commentary in measured drops, several passages toward the end of The Leopard give us a taste of things to come. In a telling comment, the prince predicts that his grandson and namesake, though born a nobleman, will be, "embittered by the gadfly notion that others could outdo him in outward show."

Following the Second World War the descendants of the Bourbons - the dynasty ousted in 1860 - were allowed to return to Italy, where their Constantinian Order, an institution marginalised in the Kingdom of Italy, is recognised by the government, counting the prime minister, generals and diplomats among its ranks. The royal dynasties of Tuscany and Parma, other states annexed as part of the unification, enjoy a similar status; officially, the Italian Republic takes a dim view of the House of Savoy, and exiled the last king in 1946. The Leopard is required reading in many Sicilian high schools, a fact which over the years has altered the popular view of the unification itself, fostering a healthy scepticism. (Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was a novelist, but historians Denis Mack Smith, Robert Katz and Harold Acton, among others, have written critically of the unification of 1860.) Perhaps the greatest virtue of the novel is that it was part of a subtle movement to address the bias intrinsic in the "official" history forced down Italians' throats beginning in 1860 and culminating with the collapse of Fascism and the monarchy some eight decades later. Vindication might be too strong a word for this phenomenon, but it did give a voice to those Italians whose views had been subsumed by recreants in a din of misplaced nationalist triumphalism. The entire perception of the Risorgimento in the flow of Italian history has changed. In his introduction to an edition of The Leopard published in 1986, the erudite David Gilmour observes that Lampedusa's view of history is no longer "a target for intellectual indignation" as it was in 1958. But for many the story is more personal, part of a Sicilian heritage. The Leopard and David Gilmour's biography of its author can be ordered on the books page. About the Author: Michele Parisi, who presently resides in Rome, has written for various magazines and newspapers in Italy, France and the United Kingdom. This article (like most of those in this online magazine) was translated from the Italian by our staff. | ||

Top of Page |

In 2009, when Sir Rocco Forte opened his resort (Verdura) along the Sicilian

coast near Sciacca, he decided to place a copy of The Leopard in

each luxurious suite. The novel about an aristocratic family is an easy

read, and no other book captures the elusive history of western Sicily during

the unification (around 1860) so concisely yet transparently. Incredibly

enough, it remains Sicily's bestselling work of fiction more than a half-century

after its initial publication. It was

In 2009, when Sir Rocco Forte opened his resort (Verdura) along the Sicilian

coast near Sciacca, he decided to place a copy of The Leopard in

each luxurious suite. The novel about an aristocratic family is an easy

read, and no other book captures the elusive history of western Sicily during

the unification (around 1860) so concisely yet transparently. Incredibly

enough, it remains Sicily's bestselling work of fiction more than a half-century

after its initial publication. It was  How relevant

is The Leopard to a balanced assessment of Italian

unification history? Today nobody contemplates Italian unification as much

more than a necessary step in Italy's slow evolution toward modern nationhood.

The unification itself did nothing to help Sicily, still crippled

by a perennially underdeveloped economy and tainted by one of the highest

levels of unemployment in the country. As a mediocre imperial power, Italy's

aspirations to greatness were swept away by the Second World War at home

and crushing military defeats in the Balkans and Africa. The monarchy was

abolished in 1946, but not before the last king made Sicily administratively

semi-autonomous, in a sense unravelling part of the fabric woven by his

ancestors in 1860, and federalism is now a political reality in Italy. (As

I write this, in 2010, Sicily's regional government is controlled by a regionalist

political party elected with a substantial majority.)

How relevant

is The Leopard to a balanced assessment of Italian

unification history? Today nobody contemplates Italian unification as much

more than a necessary step in Italy's slow evolution toward modern nationhood.

The unification itself did nothing to help Sicily, still crippled

by a perennially underdeveloped economy and tainted by one of the highest

levels of unemployment in the country. As a mediocre imperial power, Italy's

aspirations to greatness were swept away by the Second World War at home

and crushing military defeats in the Balkans and Africa. The monarchy was

abolished in 1946, but not before the last king made Sicily administratively

semi-autonomous, in a sense unravelling part of the fabric woven by his

ancestors in 1860, and federalism is now a political reality in Italy. (As

I write this, in 2010, Sicily's regional government is controlled by a regionalist

political party elected with a substantial majority.)