...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Antonella Gallo | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

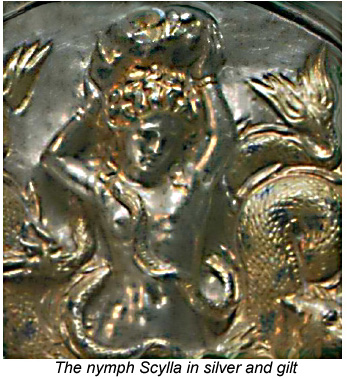

Sometime around 300 BC (BCE) Greek artisans in Sicily crafted a stunning set of silver dishes and other items, many with gilt accents and decorated with mythological figures. These were eventually purchased by a wealthy man named Eupolemos. To discourage theft he had his name stamped into a few of the pieces, which he and his wife used in their splendid home in Morgantina in east-central Sicily. Much later, this would be key to identifying the objects when they appeared farther from his home than Eupolemos would have thought possible. Founded by the Sikels, Morgantina flourished under Greek rule, though Ducetius tried to "liberate" the city in 459 BC. Morgantina continued to prosper during the rule of Agathocles (317-289) and Hieron II (275-215), when the objects may have been made in Syracuse. During the reign of Hieron, in particular, such crafts flourished there. The style is certainly similar. Having rebelled during the Second Punic War, the town (two kilometres away from what is now Aidone) was conquered and looted by Roman troops in 213 BC, but not before its citizens could hide some of their wealth. Somebody – perhaps Eupolemos himself – hid the silver objects in a shallow pit covered over with sandy soil. For some reason, many citizens abandoned the town, or perhaps their children forgot about what their parents had buried. Perhaps Eupolemos and his family were killed and their secret died with them. Maybe they were resettled or imprisoned by the Romans in a place far away. Independent records indicate that a wealthy man named Eupolemos resided at Morgantina during this period in a house very near the site where the silver was found, so it is presumed that he was the man whose name was incised on the artefacts.

What remained of once-prosperous Morgantina was sacked by the corrupt Roman governor Verres around 72 BC and finally destroyed by a vindictive Octavian some four decades later. (Cicero successfully prosecuted Verres for this and other crimes.) But for their recent discovery, the tale of the sixteen objects – including bowls, cups, serving dishes, jewellery containers, a dipper, perfume holders – would end there. What occurs next is a story worthy of Indiana Jones, but without the Nazis and guns. The fate of the objects remained generally unknown to posterity until 1984, and it is here that the story of their discovery takes an unexpected turn, and an object lesson to those institutions or individuals who acquire undocumented antiquities from "private" sources. In that year New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art announced to great fanfare its acquisition (for nearly three million dollars) of the collection from an antiquities dealer over the course of the immediately preceding years. For the Italian authorities, who became aware of their presence in New York in 1986, proving the theft was problematical: the treasure, the product of illegal excavations around 1980, had never been properly catalogued, nor had it ever been evaluated by archaeologists accredited to the digs themselves. Yet since 1980 rumours persisted in the Morgantina area of a great (illegal) find of silver objects at the site, and some of those rumours described a few of the objects in fairly precise detail. Upon investigation, an illegally excavated pit was discovered, covered by loose soil. Expecting to find, at best, some small object or coin left behind (Morgantina once boasted an important mint), investigators were surprised to uncover an Italian coin dated 1978. Other factors were instrumental in ascertaining the origin of the stolen objects, not least of which being the incised name of the owner. Eupolemos could never have imagined that his name on these objects would prove so useful so long after his death. True, the Italians could not actually "document" the ownership history of the objects, but neither could the folks at the Metropolitan Museum, who bore the burden of proof. Nevertheless, nobody had ever doubted their origin in Greece or Greek Italy. Their weights, for example, were marked with the Persian-Selucid system widely used in Greek Sicily. The collection is on display in the permanent collection at the Morgantina archeological museum. About the Author: Antonella Gallo, who teaches art in Rome, has written numerous articles on arts and artists for Best of Sicily. | ||

Top of Page |

"Buried Treasure" would not be a misplaced description for

what has been returned to Sicily after thirty years.

"Buried Treasure" would not be a misplaced description for

what has been returned to Sicily after thirty years. We'll

never know for certain, but a number of jewels and coins discovered at Morgantina appear to have

been hidden during this period, after which the city seems to have been

underpopulated for some time, becoming the home of some Hispanic soldiers from

the legions of Marcus Cornelius Cetego.

We'll

never know for certain, but a number of jewels and coins discovered at Morgantina appear to have

been hidden during this period, after which the city seems to have been

underpopulated for some time, becoming the home of some Hispanic soldiers from

the legions of Marcus Cornelius Cetego.