...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Carlo Trabia | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

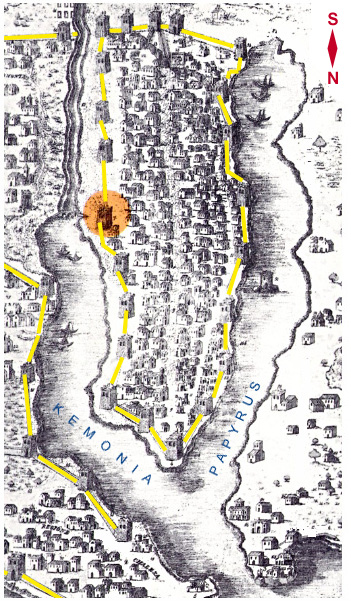

Featuring arched two-light windows and loopholes (slit windows through which arrows could be launched), the highest part of this defensive tower was constructed late in the twelfth century, during the last decades of the Norman era or the first years of the Swabian period, and the Hohenstaufen coat of arms is sculpted along what used to be its exterior (on a side not visible in this photograph). Interesting as this medievalism may be, the origins of the Federicos' distinctive tower set it apart from most others, for it was built upon one of the external walls of Punic Palermo bordering what used to be the banks of the Kemonia River. The map shown here is slightly anachronistic, as the rivers were filled in by 1300 and the coastline extended almost to its present location (the confluence of the Papyrus and Kemonia rivers was near what is now the intersection of Via Roma and Via Vittorio Emanuele), but the yellow lines indicating the city's earliest walls are essentially accurate. Of course, the Arabs and Normans enlarged Palermo and built additional walls and gates, and the city's area was further extended by the walls ordered by Charles V during the sixteenth century. However, the Punic walls, built by the Phoenicians

and Carthaginians between 700 BC (BCE) and 400

BC, supported a number of later (medieval) guard towers - if not the quantity

indicated here - and this is the last one remaining. It is highly probable

that the medieval tower itself was built upon the site of an ancient Punic

tower. In 254 BC a major battle of the First Punic War was fought here, Carthaginian

archers firing flaming arrows at the invading Romans in the river below. The story of the Federico tower's preservation is closely linked to the privatization of the Punic walls with the city's rapid expansion during the thirteenth century, when places previously outside the walls were incorporated into the city proper. Almost directly to the east (beyond the Ballarò Street Market), the wall running parallel to present-day Corso Tukory, where Saint Agatha's Gate still stands, embraced much of the expanding city in the latter years of the reign of Frederick II. The market itself has existed in some form since Arab times, and the tower of nearby Saint Nicholas Church boasts nearly the same antiquity as the newer part of the Federico tower. At some point, certainly before 1300, the tower fell into private hands and buildings were constructed around it, changing its outward appearance from that of a tower to what looked like part of a typically Sicilian noble home. This development meant that the last guard tower surmounting the Punic walls was effectively concealed and conserved. The highest part of the Federico tower looks more Swabian than Norman, and its style is not unlike that of the later (early 14th century) Chiaramontean Gothic of the Steri Castle. Right down the street, Palazzo Sclafani was constructed in a slightly more recent style. Yet there is no doubt that its lower level is indeed ancient. Nearby, in a wall along Via Protonotaro, can be observed (in a single building) Punic foundations, two eleventh-century Arabic loopholes, Norman-era arches and Swabian-era two-light windows. The Federico family was ennobled formally by feudal purchase of the county of San Giorgio and other properties in the seventeenth century. Some contemporary scholars postulated a Longobard lineage and descent from a knight named Leon of Titignan, chamberlain of George of Antioch, bastard son of Frederick II - and hence the origin of the surname. Others advanced the idea of a direct descent from George himself. One of the best pictorial and historical references on this kind of architecture and the culture associated with it is Gravett's and Nicolle's book The Normans - Warrior Knights and their Castles, which describes fortresses in Normandy, Sicily and England. About the Author: Carlo Trabia is an architect who lectures on architectural history. | ||

Top of Page |

Sicily is dotted with picturesque

towers built before 1500 as well as a series of coastal sixteenth-century

structures built as a warning system for raids by pirates - the idea being

that each seaside tower was visible to the next one in the network. Castles,

palaces, fortified walls and churches boast sturdy towers. Some aristocratic dwellings, like Taormina's

Sicily is dotted with picturesque

towers built before 1500 as well as a series of coastal sixteenth-century

structures built as a warning system for raids by pirates - the idea being

that each seaside tower was visible to the next one in the network. Castles,

palaces, fortified walls and churches boast sturdy towers. Some aristocratic dwellings, like Taormina's