...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Jacqueline Alio | ||||||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

Today, what little survives of Palermo's Judaic legacy is concealed by layers of concrete and centuries of the same ignorance that has obliterated much of the city's Muslim history. An example of the latter is the column on the cathedral's gothic portico bearing an inscription of the first sura of the Koran. A similar column is preserved at the entrance of Palazzo Steri, but a church seems a stranger place than a castle for a Koranic verse. It is quite possible that by the Late Middle Ages, when both structures were built, nobody in Sicily could translate the Arabic text; indeed it is altogether possible that none of the architects or builders even recognized it as Arabic! The same ignorance led to the street next to the site of the synagogue eventually being named Meschita (the Spanish for "mosque") instead of something more appropriate. The misnomer reflects the fact that the Palermitans identifying the square knew precious little of either Judaism or Islam, faiths which once formed the foundation of their city's culture and society, and perhaps even confused one religion for the other.

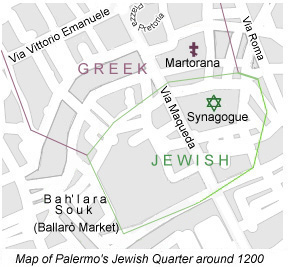

Fortunately, the archival record is well preserved. In fact, it is possible to identify many Jewish families and anusim (the "conversos" called neofiti in Sicily) who lived into the sixteenth century. What do we know of Palermo's Jews? Though they were certainly present from Roman times, it was after the fall of the Western Empire, at the dawn of the Middle Ages, that the earliest records known to us emerge. In 598 the Patriarch of Rome subsequently known as Pope Gregory the Great sent a delegation to Panormus (as Palermo was then known) to resolve a dispute involving the city's Jews; since 535 Sicily had been part of the Byzantine Empire but for a few decades its clergy answered to Rome rather than to Constantinople. We know that some local Christian priests were trying to convert the Jews, and had confiscated one of their synagogues, and that Gregory's papal bull Sicut Judeis put a stop to the coercion without discouraging voluntary conversions. Gregory, whose mother was from Palermo, took a special interest in the city but Victor, the local bishop, seems not to have heeded his orders; this should be considered in light of the fact that Sicily's hierarchy was increasingly looking to the East. In Sicily as elsewhere, the fate of the Jews was often determined by events shaped by the larger community among which they lived as a tiny minority. When Palermo fell to Arab control in 831 the Jews, like the Christians, were considered "People of the Book." They were required to wear a distinctive badge (usually a yellow cord), pay special taxes and so forth. Jews could not hold public office or serve in the military, nor could they erect new synagogues, but otherwise they were respected. Like Muslim ladies, most Jewish women wore some kind of veil in public. The vernacular dialect of the Jews of western Sicily was similar to Arabic. In 972 Ibn Hawqual, a traveller from Baghdad, visited Palermo - now called Bal'harm or simply al-Madinah (the city) - and described the Jewish community in some detail. The arrival of the Normans in 1071 saw the abolition of most restrictions, and a few Jews ended up in public administration. Certain Jewish leaders, notably the outspoken Joseph ben Samuel, initially opposed the Normans because Christians usually attempted to convert Jews, whereas Muslims didn't. Most of Palermo's Jews were traders, dyers, scribes specialized in translation, or goldsmiths. Of particular distinction we find David Ahitub (floruit 1286), a leading scholar, and Isaac Al'dahav (fl. 1380), an astronomer. The Normans and the Swabians sought to protect this religious minority. Perhaps 6% of the city's residents were Jewish. Most of the Jews lived in a partially-walled area, and until the sixteenth century a "Jewish Gate" stood in this part of the city. It is quite possible that this was the same gate, or perhaps a newer one at the same location, seen by Ibn Hawqual. During the Norman period this area was bordered by a Greek quarter and an Arab souk called Bah'lara which survives today as the Ballarò street market. Into the twelfth century the Normans permitted Greeks (Orthodox Christians), Muslims and Jews to be judged by their own courts and laws - halakah in the case of Jews. (Seeking a more uniform legal code, Frederick II greatly altered this policy.) It was during the Norman period that Benjamin of Tudela, himself a Jew, visited Sicily and described Jewish life as well as providing an informal census. According to his information, there were at least 1,500 Jewish families (each with a male head of household) living in Palermo around 1170, which implies at least 4,000 people. In 1492, the jurats of Palermo claimed there were some 5,000 Jews. A near-contemporary description of Palermo, this one through Muslim eyes, was recorded by Ibn Jubayr, who visited in 1184. He wrote that, "the Christian women of this city appear similar to the Muslims, like them they speak Arabic correctly, and they wear the veil." Comparing Palermo to Cordova, he described such features as its four rivers and - more importantly - the tower of the Martorana Church near the Jewish Quarter. Historical context and what descriptions have come down to us suggest that the basic structure of the main synagogue (which was modified over time) resembled this squarish Greek Orthodox church built nearby in the Norman-Arab style - being simple Romanesque with graceful arches and a cupola, not unlike coeval temples in Jerusalem and Constantinople. Considering their similarity of style, the exterior views of many places of worship present in twelfth-century Palermo would not permit ready distinction of synagogues, mosques and churches. The Constitutions of Melfi of Frederick II standardized Sicilian law for all subjects and addressed the specific needs of the Jews, permitting them to lend money. There had been isolated cases of forced conversions, such as a case in 1220 involving some 200 Jews, and Frederick, who was often at odds with the Papacy, sought to end such persecution. Over time the Jews began to practice ever more specialized professions; by 1400 it appears that many of the best physicians in western Sicily were Jews. At least a few Jewish men owned landed estates, mostly small feudal manors rather than larger holdings such as baronies. While Sicily was dotted with small Jewish congregations, those in Palermo, Siracusa, Trapani and Messina were important points of reference for the more isolated ones. It used to be presumed that medieval Jews were not aristocrats. Recent research indicates that by the Late Middle Ages a few Sicilian Jews had been ennobled ipso facto through the purchase of feudal property, effectively constituting a tiny segment of the Sicilian aristocracy. They were among the first Jews in Europe to enjoy such a distinction. Rule by Aragonese and Spanish dynasties began with the Vespers in 1282. By then, with the Muslims gone or christianized, and most of the Greek Orthodox Christians having over time become Roman Catholic, the Jews were the last ethno-religious minority in Sicily (though a few communities of Albanian refugees were established in Sicily late in the fifteenth century). Unfortunately, their rights were gradually curtailed. No longer could they be said to be treated as the equals of their fellow citizens. Early in the fifteenth century, for example, yeshivas came under stricter control by the Crown, and in 1467 a heavy fine was levied upon Palermo's Jews for having restored the chief synagogue - the construction and restructuring of synagogues having been outlawed unless prior authorization was granted. Moreover, they were highly taxed. Yet in 1487 the visiting Ovadyah Yare of Bertinoro wrote a description that began, "Palermo's synagogue is without equal the world over..."

Absentee rule (from Spain) and the zealousness of the Inquisition, among other factors - such as an aristocracy bent on exploiting the island's poor - left Sicily in an intellectual stupor by 1400, threatened by a frightening level of illiteracy that worsened over time, reaching 85% by 1800. Matters were equally deplorable throughout Italy. The Jewish communities were a stark, welcome exception to this destructive trend. The infamous edict of 1492 prompted the expulsion or - perhaps just as often - conversion of Sicily's Jews, who by then numbered at least 20,000 (and perhaps as many as 40,000). Their absence has been felt ever since, and tracing Jewish roots in Sicily remains a challenge. Several riots by converted Jews broke out in the years to follow, with a particularly violent incident reported in Palermo in 1516. The road to Christianity and the Catholic Church was often a difficult one, and not always a desired one.

Editor's Note: The picture (above) shows what the principal synagogue probably looked like during the Norman period, before its modifications two centures later, which were likely consistent with the Catalonian-Gothic style then in vogue. This image is based on Palermo's Norman-Arab architecture and what we know from contemporary descriptions of the structure and its gardens. About the Author: Historian Jacqueline Alio wrote Women of Sicily - Saints, Queens & Rebels and co-authored The Peoples of Sicily - A Multicultural Legacy. | |||||

Top of Page |

The

The  What we find in Palermo is the occasional Hebrew inscription in a church

or palace that was standing in 1492. The site of the chief synagogue - where

a church now stands - is readily identified. Although the

What we find in Palermo is the occasional Hebrew inscription in a church

or palace that was standing in 1492. The site of the chief synagogue - where

a church now stands - is readily identified. Although the  Observance of Sicily's earliest Jews, part of the Diaspora, was akin to that of the Mizrahim

of Tunisia. Their identification today as Sephardic would not be very accurate historically before

the reign of

Observance of Sicily's earliest Jews, part of the Diaspora, was akin to that of the Mizrahim

of Tunisia. Their identification today as Sephardic would not be very accurate historically before

the reign of