...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Jacqueline Alio | ||||||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

Indeed, this is the oldest mikveh (or mikvah or miqwa) known to survive in Europe. By definition, a mikveh is a ritual bath, consisting of at least one pool but perhaps several. The mikveh is an important part of Jewish tradition, and it was the inspiration - or at least the precedent - for analogous practices in Christianity (Baptism) and then Islam (Ghusl). Whereas Baptism is a sacrament that is performed only once (originally by full immersion as it is still practiced in the Eastern Orthodox Churches), Ghusl customs are more similar to Judaic practice. Obviously, one form or another of ritual bathing is a shared legacy of all three Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, ritual bathing, or ablution, in the form of tevilah (full-body immersion) in fresh water, may date from Mosaic times, and has certainly been practiced since the period during which the Book of Leviticus was authored, before 322 BC (BCE). Both the Mishnah and the Talmud refer to the practice, and many Jewish rituals are rooted in this era. The Jewish congregation of Syracuse was probably the first to be established in Sicily, and one of the first few in what is now Italy. Judaism was present here long before the arrival of Christianity on Sicilian shores. The first Jews of Sicily were present during Roman times (archaeological evidence indicates that a community of the Samaritan sect also flourished in Syracuse). It is thought that while in Syracuse circa AD (CE) 59, Paul of Tarsus preached to Jews as well as Greeks. Of particular note, a few Jews arrived as slaves following the Siege of Jerusalem a decade later in AD 70 during the First Jewish-Roman War (The Great Revolt), commemorated in Rome's Arch of Titus where one of the earliest depictions of a menorah appears as a spoil of war. However, the greatest influx of Jews took place in the decades immediately after 135, in the wake of the Romans' complete expulsion of the Jews from the holy city of Jerusalem after Bar Kokhba's Revolt (which began in 132) during the rule of the emperor Hadrian. Thus whatever semblance of Jewish independence had ever existed under the Romans was lost. This led to the Diaspora. Though Syracuse had been a Roman city since 212 BC, its culture and principal language were Greek throughout the Roman period. With the arrival of the Jewish refugees, Aramaic was added to the linguistic mix. Most of the city's Jews resided in their own quarter and for many centuries their lives were governed by their own law. The mikveh was part of it. The mikveh of Siracusa dates from the Byzantine period following the fall of the "western" Roman empire to invading forces (in Italy mostly Vandals and Visigoths) in the fifth century. In 535, the Byzantine general Belisarius seized control of Sicily from the Goths. In 598 the Patriarch of Rome, Pope Gregory the Great, with the Papal bull Sicut Judeis, ordered Sicily's bishops to protect the island's Jews from persecution and forced conversions. It was probably around this time that the mikveh we see today was carved into a limestone hypogeum over twenty meters below ground level, but circumstances suggest an earlier date. In 655 Ortygia's Jews obtained permission to rebuild the synagogue that had been destroyed by the Vandals. Had their mikveh also been destroyed by the invaders, or was it spared? The latter hypothesis leaves open the possibility that the hypogeum we see today already existed in 535 when the Byzantines arrived. At all events, it was almost certainly in use when the Emperor Constans ruled the Byzantine Empire from Syracuse from 660 until 668. Another noteworthy hypogeum in the central Mediterranean designed for religious use, and in that sense comparable to the Syracusan Mikveh, is the much-larger al-Saflieni Hypogeum carved on Malta beginning around 3300 BC. A mikveh is, of course, a sacred site, though not a place of worship. A spring supplies water to the mikveh's five immersion pools. It has been suggested that the same underground spring feeds the Fount of Arethusa. There is even a vent running from the hypogeum's ceiling to ground level. Medieval oil lamps were discovered during the excavations.

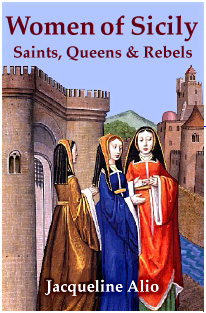

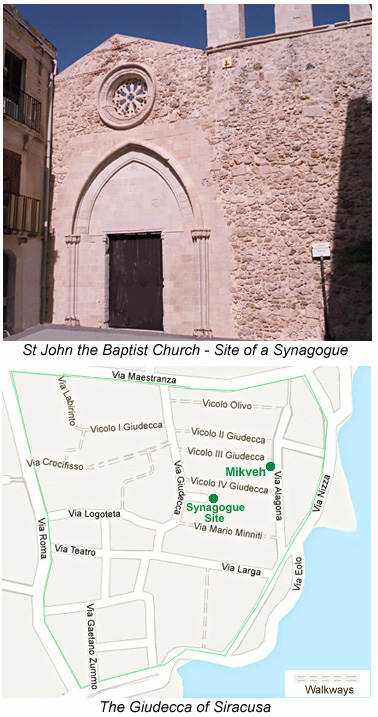

In medieval Judaism the mikveh was just as important as the synagogue. Customarily, a new Jewish community would invest in its mikveh before allocating funds for the synagogue or Torah scroll. It is possible that a synagogue once stood atop the mikveh, though it is equally likely that the first chief synagogue (there eventually may have been two or more as the Jewish community grew) was located nearby, probably on or near the site of Saint John the Baptist Church - which by tradition is said to be the place where Saint Paul preached. The Jewish market is thought to have stood where Saint Philip's Church was erected, and here, under the crypt, are the remains of another mikveh. Full of medieval buildings, the Giudecca of Syracuse is a labyrinth of narrow medieval streets and walkways. The mikveh of Syracuse has a total of five immersion pools. There are three triangular pools in the main chamber, where there is also a round pool that serves as a reservoir. On each side of the main chamber is a small side chamber having a square pool; these were used by priests or other important individuals, almost exclusively male. There were probably days the mikveh was open to women, and others for men. Historically, wine vessels and eating utensils, if acquired from a Gentile, had to be immersed in a mikveh before their first use by Jews. Here we are describing usages from Sicily's Byzantine period until the fifteenth century. In 1492, with the Kingdom of Sicily under Spanish rule, King Ferdinand issued the infamous edict ordering the expulsion or conversion of the island's Jews. In fact, many converted to Catholicism. During the Late Middle Ages (circa 1400), by the most reliable estimates, as much as one-quarter of Ortigia's population, or as many as 5,000 families, was Jewish, and most lived in the Giudecca. More than half these families left Sicily in 1493. Those who remained became Christians - the anusim known in Sicily as neofiti, and in Spain as marranos or conversos. It would seem that these converts, whatever their number, chose not to reveal the existence of the mikveh. At some point their secret was forgotten. In many cases churches were built on the sites of synagogues during the next century, just as they had been constructed on the sites of mosques during the thirteenth century when Sicily's last Muslims had converted to Catholicism. Somehow, Syracuse's Jews managed to bury this mikveh, in Via Alagona (the Church of Saint Philip was later built over the other one), in soil and fine sand without their being discovered by the Spanish authorities. Incredibly, the Inquisition seemed ignorant of the mikveh's subterranean existence, partly because changes in government (viceroys) were frequent, and though the Giudecca was not a walled community, Gentiles were not permitted in the mikveh and few ever entered a synagogue. In 1493, Judaism's presence in Sicily disappeared almost overnight. It is believed that the Bianca (or Bianchi) family that resided in the house above the hypogeum during the sixteenth century was anousim, having converted from Judaism to Christianity. Discovered only some 500 years later, the "secret" mikveh still utilizes its original water supply. Its discovery and excavation is perhaps the most fascinating part of its story, one of the things that makes it a rare treasure. We know that by the fifteenth century Palermo's Jewish community was larger than that of Siracusa. The Palermitan Mikveh was built before the Norman conquest of that city in 1071, probably during the tenth century, supplied by the same spring that fed the Kemonia River through the Arabs' highly sophisticated system of underground kanats.

Unlike other early-medieval mikvehs excavated in Europe (Cologne's comes to mind), the "Casa Bianca" mikveh in Via Alagona has actually been used by members of the Jewish congregation in recent years. As one of the oldest mikvehs in use, it is much more than an archeological curiosity. It is a living legacy. • Visiting the "Casa Bianca" Mikvah: The

Syracusan Mikveh is located beneath a

beautiful 17th-century residence which is now the Hotel alla Giudecca, at Via

Alagona 52. Like the hotel itself, the hypogeum is privately owned and administered (more efficiently than most of Sicily's

publicly-operated historical sites). Guided visits are scheduled most days, usually at the top of the

hour, from 11 in the morning until 5 in the afternoon. Admission is 5 euros

per person. Photography is permitted only with special permission but the hotel has

postcards of the mikveh on sale. Access to the subterranean chamber is via a series of

stone steps, conditions which should be taken into careful consideration

by those having mobility limitations or problems in enclosed areas. For a group of more than 8 visitors to see the mikveh, you

should contact the hotel in advance at allagiudecca@hotmail.com or +39 0931 22255. About the Author: Historian Jacqueline Alio wrote Women of Sicily - Saints, Queens & Rebels and co-authored The Peoples of Sicily - A Multicultural Legacy. | |||||

Top of Page |

The island of Ortygia is an ancient district

of

The island of Ortygia is an ancient district

of  The mikveh was used most often by women,

especially following menstruation

or childbirth but also brides just before marriage. Men sometimes bathed in it to achieve

purity following intimate relations with their wives, and bridegrooms bathed just before marriage. Immersion

was part of the rite of conversion to Judaism by Gentiles (in this way Baptism is very similar to tevileh), and priests bathed

during consecration and in preparation for performing certain rites. Bathing in a

mikveh was required after contact with a corpse. The purpose of immersion in the mikveh was not

physical cleansing - one must be clean before entering - but achieving spiritual purity or renewal.

The mikveh was used most often by women,

especially following menstruation

or childbirth but also brides just before marriage. Men sometimes bathed in it to achieve

purity following intimate relations with their wives, and bridegrooms bathed just before marriage. Immersion

was part of the rite of conversion to Judaism by Gentiles (in this way Baptism is very similar to tevileh), and priests bathed

during consecration and in preparation for performing certain rites. Bathing in a

mikveh was required after contact with a corpse. The purpose of immersion in the mikveh was not

physical cleansing - one must be clean before entering - but achieving spiritual purity or renewal.