...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Vincenzo Salerno | ||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

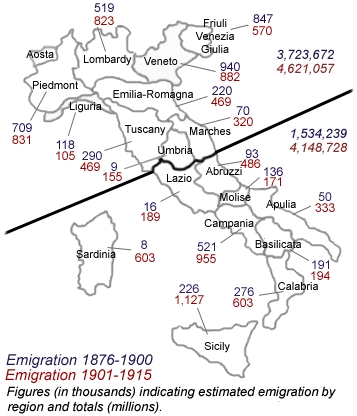

The greater part of the Italian "diaspora" was a product of the latter decades of the nineteenth century. Until around 1880, most Italian emigration was from the north: Piedmont, Lombardy, Liguria. (For approximate figures based on an Italian study, which draws the statistical line at 1900, see the following emigration map.) Before the annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily) to the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, and the transfer of Neapolitan gold deposits to Turin and then Rome - Naples was by far the wealthiest city in Italy while Palermo was actually wealthier than Milan - the people of southern Italy were no poorer than those in the north. With unification, the economy of what became "the South" worsened. This prompted mass emigration, mostly to the Americas. Before 1880, poverty and illiteracy were equally distributed throughout Italy; the most obvious distinction among the rural poor was that Piedmontese farmers grew rice, Lombards grew corn (maize) and Sicilians cultivated durum wheat. All had large families of shoeless children, something recounted most poignantly by Angelo Roncalli (later Pope John XXIII) who was raised (on polenta) near Bergamo east of Milan. This wasn't an exclusively Italian phenomenon. In fact, most of Europe suffered serious class division.

The description of Italian and German diaspora populations as "regionalist" is a misnomer because until the nineteenth century the territories of these nations were a patchwork of various states which had existed since the Middle Ages (Germany was unified in 1871). A person whose family lived in Sicily or Bavaria for generations was part of a distinct national culture spanning centuries. The Kingdom of Sicily was founded by Roger II in 1130 and had already been a sovereign "county" ruled by his Norman dynasty - beginning with his father Roger I - for some seven decades. Though it was later ruled from Madrid or Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily survived in some form until 1860. It had its own parliament, nobility and peerage. Sicily also has its own language and cuisine. It even has its own breed of dog, the Sicilian greyhound. Unlike some Italian regions, it was an actual country. So pervasive has been Italy's historical revisionism since 1861 that few Sicilians of any stripe know that the last king born on our island was not a medieval monarch but a relatively recent one, Ferdinando II Bourbon of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily). He was born in Palermo, then still the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily, in 1810, reigned from 1830 until 1859, and spoke Neapolitan as his mother tongue. This is not an argument against Italian unification in some form or a plea for monarchy in any form. However, a federalist union (perhaps a republic) launched at the inception of Italy's unification might have maintained a more uniform standard of education and economic prosperity for all of its peoples, be they Lombards, Ligurians, Tuscans or Sicilians. While it may present information with which some readers are unfamiliar, the following commentary is not misplaced nostalgia or fantasy. The items in our list of economic-industrial facts and figures regarding the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies at the time of unification in 1860 are easily verified in historical records. Today the largest number of persons (outside Italy) of Sicilian ancestry through at least one grandparent is found in the United States, followed by Argentina, Canada, Venezuela and Australia. Though our comments are necessarily general, we may look to the United States, in particular, as an exemplar in fostering the growth of an Italian (or Sicilian) diaspora because in that nation integration, assimilation, amalgamation and socio-economic opportunity are generally more readily attainable than elsewhere. Equally as significant, time forms the backdrop for a few of these observations, and more than a century has elapsed since the first major influx of Italians into the United States circa 1890. Incidentally, at least 30% of the Italians who arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1930 were from Sicily. Assimilation into one country is not necessarily as seamless as it might be in another. Latin America - with its Romance languages related to Italian and its dialects - has always been an alluring destination for Italians. So many boatloads of Italians arrived in Argentina during the 1950s that the composition of the country (formerly mostly Spanish and native or "Indian") changed within two generations; today Argentines collectively have more Italian blood than Spanish. The French culture of Quebec may have facilitated Italian immigration to that region during the same period. Ethnic identity is sometimes more complex than it seems, and it's usually rooted in a certain degree of perception. Setting aside the science, a few simple examples will suffice here. A few years ago, an American reality show participant stated that she was proud to be "Italian." She was actually an adoptee whose Sicilian surname was that of her adoptive father. Adoption is great, but it doesn't literally transfer a parent's ancestry to the adopted child. Another American "personality" is very proud of her Sicilian roots through a grandparent, but is rarely identified in the popular mind as an "Italian" even though she speaks the language proficiently and has worked in Italy. We're thinking of Paris Hilton. Then there is 25 year-old Yasmin. Born in Palermo to Moroccan parents, she speaks Italian, has Italian citizenship and was educated here in Italy. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most "Sicilian" of all?

As if this were not complicated enough, the Sicilians themselves probably descend from a greater number of ethnically distinct peoples than any other population of Europe, and have the multicultural history and genetic diversity to prove it. To identify Sicilians as just another regional population of "Italians" is a gross oversimplification. As a nation-state, Italy was established only in 1861 following a bloody war of conquest. Germany, in contrast, was united ten years later in a comparatively facile movement, and even the Germans acknowledge that there are subtle cultural differences between Prussians and Bavarians. Critics might argue that Italy existed in antiquity. The Italian peninsula was the Roman province, and Greek Sicily in turn the first province of Rome. True, the Lombards ruled much of peninsular Italy for a time, but they had to share it with the Byzantines and the Popes before losing it to the Normans. Then Frederick II ruled Sicily and most of Italy and Germany for a few decades. Dante and Boccaccio wrote in Italian, then a "new" language, and people referred generically to "Italy" as, in the eternal words of Metternich, "a geographical expression." But even the most recent surveys tell us that the majority of Italians identify themselves firstly by their region of birth and only secondly as Italians or Europeans - and some actually place "European" before "Italian." This begs the question of personal "ethnic" identity. Where does it begin or end? The adoptee who knows no other culture but is raised by Sicilians (in Sicily) from a young age could be forgiven for wanting to call himself a Sicilian, but what about the biological child of a sperm donor of Sicilian ancestry in the United States? "Self identification" seems to be the order of the day when an Italian-American organization grants university scholarships to students who can claim "Italian ancestry" through a minimum of one grandparent without even documenting proof of that descent. Meanwhile, persons claiming American Indian ancestry for similar scholarships must demonstrate genealogical descent from at least one Native American ancestor of a recognized nation. Are Italians outside Italy even a legitimate diaspora? They can hardly be considered a "community." Returning to the American example, there clearly is no social cohesion among Italian descendants any more than there is among German or Irish descendants. At best, there is an abstract commonality based on things like cuisine and perhaps religion (though Italy has always had religious minorities, most notably Waldensians and Jews). This is mostly due to assimilation and amalgamation ("intermarriage") in American society. There is not - and perhaps never has been - an "Italian-American voting bloc." Recent surveys indicate that Americans of Italian ancestry are about evenly divided among Democrats, Republicans and independent voters. Roman Catholics used to be a voting bloc, after a fashion. The Kennedy presidency appealed to Catholics across the board, not only to Italians, although Jackie Kennedy's Italian was almost as good as her French, and she spoke it when campaigning in Italian neighborhoods. But today even Catholics don't vote as a bloc or on "single issues." Most diasporas are eclectic. Though united by a single ancient religion and many traditions, the Jewish diaspora has religious and social divisions within it, and if Italians were (and are) divided in Italy it is unsurprising that they would have difficulty uniting anyplace else. There's a saying that when two Italians enter a room and discuss something, they leave with three or four opinions. Ethnic stereotyping is viewed in a negative light precisely because it defines people based on perceived collective characteristics rather than individual ones. Two or three generations "isolated" from their ancestors' mother country can leave persons in an ethnic diaspora disconnected from it, susceptible to bizarre experiences with the "natives." The Siculo-American who speaks little Italian and really does not know Sicily, never having spent much time here, may be unprepared for what she encounters once she arrives - apart from the urban noise and ubiquitous chaos. When representatives of an Italian-American foundation came to Palermo to meet with Sicilian officialdom, it was obvious they hadn't been briefed about the people they were meeting. On the other hand, the professional diplomats who officially represent Americans would have been provided concise intelligence reports on every person they were scheduled to meet.

Over time, diasporas develop their own subcultures. That's how Phoenician traders in northern Africa became the Carthaginians, and Norse settlers in northwestern France became the Normans. The Italian diasporas are no exception, though they are less isolated today than they were a hundred years ago. A common criticism is that immigrant diasporas are sometimes "trapped" in the past, so an Italian-American organization might entertain a view of (for example) the Italian unification movement that seemed accurate enough circa 1900 but is now out of step with the consensus of European scholars writing for peer-reviewed journals. Since the 1980s, most of the more insightful books dealing generally with recent Italian history (or specifically with Sicily) have been published in Britain and, of course, here in Italy. Most modern democracies attempt to ascribe to each citizen a social status based on something other than his ancestry (genealogical lineage) or ethnic background. Over the last century or so, many volumes, and much legislation, have been dedicated to achieving that lofty goal, and Britain has greatly reformed its House of Lords to reflect such attitudes. Clearly, questions of ethnicity and ancestry must be placed in perspective because they come to us at random. Nobody selects his ancestors. This may explain why the intrinsic exclusivity of hereditary or lineage societies (the Order of Malta in Italy, First Fleet in Australia, the D.A.R. in the United States) evokes ambivalent feelings in some citizens. It can appear to be an attempt to derive personal prestige for something an ancestor did. That's why the recognition of titles of nobility was proscribed by the American Constitution and (in 1948) by the Italian one too. Diasporas can be more ethnocentric than the ancestral societies they came from, so certain Americans are "more English than the English." The people of Italy seem not to be obsessed with Italianità. Here in Italy the Italianista is usually viewed suspiciously by the larger society as a xenophobe or even a neo-fascist reluctant to embrace a reality beyond the shores of a country which comprises less than one percent of the world's population, even moreso if he refuses to learn English. One may love her own ethnicity and ancestors without being obsessive about what is essentially an accident of birth rather than an accomplishment or personal choice. Ancestry is not destiny; the fact that a jailed American murderer is descended through twenty generations from an English king makes him no less vile. Viewed from the opposite end of the telescope, a criminal's illustrious lineage will be insufficient to save him from prosecution unless he can transport himself back to the Middle Ages when such things really mattered. Apropos kings, the reason historians often point to the aristocracy in discussions of national identity is that this class was influential historically and is readily identified, whereas the names of common folk are largely forgotten. That said, many Italian traditions, be they literary, musical, culinary or religious, emanate from the less exalted social classes from which most descendants in the Italian diasporas descend. Today Italy suffers a Brain Drain, but in times past immigrants to foreign shores did not always enjoy the benefit of extensive education in their countries of birth. While this partly explains a certain lack of a "continuity" in knowledge about Italy over three or four generations in the diaspora, it is no excuse for an American or Australian descended from one or two Italian grandparents to avoid reading about his ancestors' place of birth. This is really a simple question of curiosity. People raised in Sicily are taught Sicilian history. They at least know that the triskelion is the island's symbol, that Sicily had the first constitution of the Italian states (in 1812), and that the Bourbons and other (more distinguished) dynasties once ruled here. Those raised outside Italy seem to lack a "canon" or "syllabus." Books dealing with Sicily are mentioned all over this site and on this page. As an introduction, we recommend Denis Mack Smith's History of Sicily as a solid foundation for further reading, published as one volume or a more detailed two-volume edition. For modern Italian history the best book is David Gilmour's insightful The Pursuit of Italy: A History of a Land, Its Regions, and Their Peoples. We list a few books below and on our pages about Sicilian identity and the Sicilians. It is unfair to make direct comparisons with the Jewish Diaspora, which uniquely constitutes the de facto global identity and society of a displaced people, but what stands out among the Jewish communities is a serious effort at "ethnic" education which in the Italian "diasporas" is at best an isolated phenomenon (mostly scholarship grants) and not community-based. The Birthright Israel program comes to mind. Significantly, a young person need not be "selected" for the Israel experience in the manner of a scholarship or other privilege because it is based on the very fact of his being Jewish. Since "ethnic" identity is based on history, ancestry, culture, upbringing, education and other factors, rather than "recognition" or "certification" by any "authority" - and since diaspora Italians per se cannot be identified in the same way as Jews (birth to a Jewish mother), Arabs (native speakers of Arabic) or Catholics (baptism) - a few observations present themselves. • It should be obvious that the overwhelming majority of Italians in any "diaspora" have nothing to do with ethnic clubs. Were it otherwise, such organizations in the United States would boast at least 20 million adult members, which is far from the case (it is estimated that about 8% of Americans of all ages have some Italian ancestry). By way of analogy, not every university graduate belongs to an alumni association.

• Emigré groups the world over spawn their own subcultures of self-centered or revisionist ideas developed independently of the mother culture. Among diaspora Italians, "Garibaldi was great" and "there's no Mafia" seem to be popular mantras. Don't let a group of apologists think for you. Italian books, websites and newspapers are a better source of Italian information than any single organization. Visit Sicily for at least a week at some point in your life, just to get a clear idea of this place and its people. And perhaps even yourself. • Being "Sicilian" or "Italian" is not based on citizenship. A Canadian, Australian or American can have a family tree full of Italian ancestors without being a citizen of the Italian Republic. • We've generalized here, but each diaspora has its peculiarities. In Argentina the population of Italian origin is much higher than the United States' 7 or 8 percent. • Despite what certain genetic genealogy firms may tell you, there is no "genetic profile" for Sicilians, or for Italians generally. As regards Sicilian population genetics, diversity is the rule, and in either the male line (Y chromosome) or female line, haplotypes and haplogroups reflect colonizations as recently as the Middle Ages. • Interesting though genetic profiles are, the best way to discover Sicilian family history is through documentary research, and Sicily offers the world's best genealogical records. In Sicily it is not unusual to trace the generation-by-generation, father-to-son lineage of an ordinary (non-aristocratic) family to circa 1500 - something rarely possible elsewhere. • One need not be Italian to be an Italophile, and in the 21st century the natural curiosity of a person (outside Italy) having no Italian ancestry who loves Italian culture should be recognized, as opposed to the indifference of an Italian descendant. The non-Italian Italophiles represent the true spirit of medieval, multicultural Sicily and Renaissance Italy. Like the legacy of the ancient Romans, Italian culture belongs to the world, not to one ethnic group. • Nobody has the authoritative "last word" on who is (or isn't) Sicilian, or on what it means to be a Sicilian. Not politicians, anthropologists, historians or sociologists. And certainly not us. Further Reading About the Author: Vincenzo Salerno has written for this magazine and others. Thanks to Luigi Mendola for his assistance in research and editing. | |

Top of Page |

A particular myth about the people of the

A particular myth about the people of the  Citizenship is our modern way of identifying somebody as part of a national

group, yet most would agree that the American citizen descended from four

Italian grandparents has some claim, at least on a purely cultural level,

to being "Italian." After all, nobody can deprive him of his ancestry

and heritage. Unlike the Italians, certain cultures have standards of identification

that transcend modern borders. Any Jew born to a Jewish mother is a Jew,

even without religious observance, and nobody can deprive him of his being

Jewish. Arabs, by definition, are those who speak Arabic as their mother

tongue or are born in an Arab-speaking country. Yet nobody claims that the residents of Ticino (in Switzerland) are

Italian just because they speak Italian, or that the Italians of Bolzano

(in South Tirol) are Austrians simply because they speak German.

Citizenship is our modern way of identifying somebody as part of a national

group, yet most would agree that the American citizen descended from four

Italian grandparents has some claim, at least on a purely cultural level,

to being "Italian." After all, nobody can deprive him of his ancestry

and heritage. Unlike the Italians, certain cultures have standards of identification

that transcend modern borders. Any Jew born to a Jewish mother is a Jew,

even without religious observance, and nobody can deprive him of his being

Jewish. Arabs, by definition, are those who speak Arabic as their mother

tongue or are born in an Arab-speaking country. Yet nobody claims that the residents of Ticino (in Switzerland) are

Italian just because they speak Italian, or that the Italians of Bolzano

(in South Tirol) are Austrians simply because they speak German.