...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Carlo Trabia | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

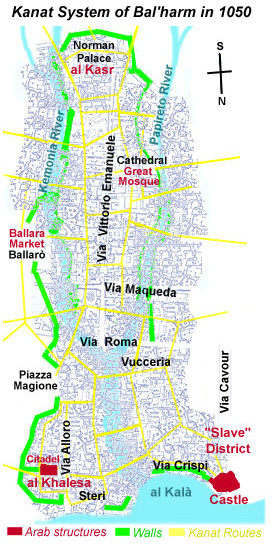

The Aghlabid invasion force of some ten thousand men that landed near Mazara with Hassad ibn al-Furat in June 827 (arriving from Susa in Tunisia), included Arab, Berber and Persian Muslims. Over the next two centuries, they were followed by thousands more, and every aspect of Sicilian society was drastically altered - from cuisine to religion to language. Architecture was also influenced. Today, it's easy to point to the "Norman-Arab" style which led to the design of churches that looked like mosques, but this was primarily a twelfth-century movement. Long before that time, the Saracen Arabs planned entire cities based on patterns popular in the Arab world. In practice, many of these developments reflected engineering popular in Baghdad, Alexandria and elsewhere. Irrigation and water supply systems were part of this. Aqueducts, of course, had existed in Sicily since Roman times, if not earlier. Parts of a Roman aqueduct are still visible in the Sicilian town of Termini Imerese, for example, and the city of Rome was itself supplied water by a sophisticated series of aqueducts. The Arabs, however, expanded irrigation to the extent that crops requiring more water than almonds, olives and hard wheat could now be grown on a large scale. Cultivation of sugar cane, lemons, oranges and mulberries became popular during the Arab period. Even rice was grown in the Aghlabid emirates of tenth-century Sicily. It is no coincidence that certain Sicilian words relating to irrigation derive from Arabic; a gebbia is a pool or small reservoir constructed of stone. But it was in the urban setting that the greatest feats of construction were to be seen (literally "seen" by few, as these were often underground). Punic Palermo could rely largely on its rivers for fresh water; this was no longer the case in the greatly expanded city of the Arabs. Under the Arabs, Bal'harm (Palermo) became the largest of Sicilian cities. Indeed, it was the Arabs who made it the island's capital, which under the Byzantines was Syracuse on the Ionian coast. Estimates of the expansive city's Saracen-era population vary widely, but two hundred thousand is perhaps a reasonable figure if the entire area is taken into account. Water supply was obviously an important problem in medieval Palermo, one of the largest European cities of the tenth century. The solution was a series of channels that brought water from springs in the Monreale area into the city. A few of these springs - one of which fed the Kemonia River - still run under the old city today. Most of the channels extended northward from the Baida and Altofonte districts, still known today for their mineral springs, across vast rural and wooded areas to the south of the city. Under the Normans, these became vast royal reserves and hunting grounds of the Genoard Park (there were some Phoenician and Carthaginian burial sites in the area immediately south of al Kasr), and the water supply was still protected. A few of the surface channels used for irrigation can still be seen in this area.

One of the Kemonia's springs and its kanats flowed directly under Palermo's Jewish Quarter, supplying the mikveh (ritual bath). Though the Syracuse mikveh is Europe's oldest, that of Palermo - dating from the ninth or tenth century - has also been identified. In fact, fresh water still flows through some of the channels. Several were still in use well into the sixteenth century, long after the Arabs had melded into the general Sicilian population. The Arabs' descendants may have forgotten about their medieval ancestors, and even modified many Norman-Arab buildings beyond recognition, but the kanats survived. It has even been suggested that the Beati Paoli might have used some of the subterranean passages to mysteriously vanish into the night. What is remarkable is how little the fundamental principles of this kind of engineering have changed over the centuries. The materials are different, but while flow mechanics have remained constant, gravity-fed systems are no longer the only approach to designing water delivery systems. To facilitate water flow, the kanats in the Kalsa area in the northern part of Palermo were much deeper than those further inland, to the south, and a few were in use long after the Norman-Arab era. A kanat visible beneath a restaurant in Piazza Marina supplied water to the Steri Castle during the fourteenth century. While the kanat system was a project in continual development and evolution, its existence is mentioned in documents recorded during the rule of Abdullah ibn Ibrahim around 900. Most of the channels shown on our map were in use by 1050, extended during the Norman era beginning in 1071. It appears that at some point before that date the lower courses (in the city) of the two rivers were filled in but we don't know precisely when, and the location of the Papyrus (Papireto) river bed is evident today as a recession running from Via Venezia into the Vucceria street market (crossing Via Roma). By around 1000, the Cala bay had been displaced northward as the Mediterranean receded and areas formerly underwater were developed into al Khalesa (now the Kalsa quarter) and the seaside castle was constructed. In Punic and Roman times the coast was much nearer the point of confluence of the two rivers, a site now located near the intersection of Via Roma and Via Vittorio Emanuele. Unfortunately, efforts to open the kanats to guided tours have not proven entirely successful, but the existence of such passages reminds us that many of Bal'harm's secrets are yet to be revealed. About the Author: Architect Carlo Trabia has written for various magazines and professional journals, as well as this online magazine. | ||

Top of Page |

Nowadays, the supply of drinking water is taken for granted in large cities, but in the Middle Ages bringing water to thousands of people was not always a simple task. In Sicily, an

Nowadays, the supply of drinking water is taken for granted in large cities, but in the Middle Ages bringing water to thousands of people was not always a simple task. In Sicily, an  In the city, the channels were constructed far underground, carved into the dense limestone bedrock. This was practical to avoid the potential contamination of above-ground networks, and for convenience, but it was also necessary for the channels to become gradually deeper to permit gravity-based water flow - the same principle

employed in the Romans' aqueducts. The Arabs used the term kanat

(qanat) to describe these channels, and several still exist today in the

area between the royal palace and the Quattro Canti. The network was greatly expanded in the time of

In the city, the channels were constructed far underground, carved into the dense limestone bedrock. This was practical to avoid the potential contamination of above-ground networks, and for convenience, but it was also necessary for the channels to become gradually deeper to permit gravity-based water flow - the same principle

employed in the Romans' aqueducts. The Arabs used the term kanat

(qanat) to describe these channels, and several still exist today in the

area between the royal palace and the Quattro Canti. The network was greatly expanded in the time of