...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Luigi Mendola | ||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily |

The convening of the Council of Trent, a move signalling the beginning of the Counter Reformation, and the founding of the zealously anti-Reform Society of Jesus (Jesuit order) in Spain, were both supported by Charles. With the suppression of the Jews, Sicily became exclusively Catholic. Nevertheless, the Albanian refugees settling in Sicily fleeing the Turkish advance through the Balkans were permitted worship in a new "Eastern Rite" under the Papacy, so while true "Orthodox" churches were eventually prohibited during Charles' reign at least the Byzantine liturgical tradition survived. In Sicily, the zealous Jesuits never truly rivalled the Dominicans in power or prestige, and late in the eighteenth century a Bourbon monarch actually expelled the order, confiscating their estates (Casa Professa is their great Sicilian church); they returned a few decades later in a much diminished role. The Sicilian view of Charles is reasonably sympathetic. Indeed, at this distance of time it is even favorable, though Sicily was largely overlooked and generally overtaxed during his reign, even if the nobles were placated with the occasional parliament. During his reign the island was still politically independent of the peninsular Kingdom of Naples which Charles also ruled, and still significant in European politics. Toward the end of his reign this was changing as the New World moved toward center stage, leading to the relative decline of Mediterranean importance. Unlike most subsequent Hapsburg Kings of Spain who were also Kings of Sicily, Charles actually visited the island, even if this resulted from such events as his Tunisian campaign rather than from any obligation he felt to the Sicilians, who provided troops, ships and money for his adventures abroad. At least one historian refers to Charles as the last medieval knight (so depicted in the painting shown here), and it is true that the monarch continued a kind of Crusader tradition. It was he who ceded Malta and Gozo to the Knights of Saint John (Hospitallers) as part of a feudal vassalage that was to last for the better part of three centuries. Despite popular conceptions to the contrary, Malta was a dependency of the Kingdom of Sicily until it was seized by the French and then the British. It was under Charles that one began to speak of a Spanish "Empire" to rival the German "Holy Roman" Empire, though Charles actually ruled both. Before considering his impact on Sicily, let's cast a glance over the life and rule of Charles V. Charles, who was born and raised in the Low Countries, was the oldest son of Philip "the Handsome" and Joanna of Castile. Upon Philip's death in 1506, Charles succeeded him to the Dutch Crown (of the so-called Burgundian Netherlands). A decade later, with the death of his mother's father, Ferdinand the Catholic, Charles succeeded to the Spanish and Sicilian crowns but during his minority Joanna ruled as de facto regent. In 1519 he succeeded his father's father, Maximillian, as Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria. At that point Charles ruled "the empire over which the sun never sets" long before the British Empire earned that description. This realm included lands as distant as the western coasts of America (subduing both the Aztecs and Incas) and colonies in the Far East, such as those in the Philippines. Charles had to dedicated much of his reign to the "Italian Wars" against the French kings who sought control over northern Italy. This led to the bizarre Franco-Ottoman alliance against him. Suleyman the Magnificent conquered Hungary in 1526 after defeating the Christians at the Battle of Mohács, but his advance was stopped at Vienna by Charles' armies in 1529. In opposing the Reformation - yet maintaining peace with England - Charles challenged several popular movements (such as the German Peasants' War) and the federation known as the Schmalkaldic League. As a result of this experience, and hoping to discourage Protestant power, he supported the Council of Trent, signalling the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. The Jesuits, a missionary and teaching order founded in Spain during Charles' reign, were an attempt to respond to Protestantism peacefully and intellectually, but a side-effect was that a form of the Inquisition was introduced in the New World. There were some compromises, however. Though Charles personally defeated the Protestants at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, he legalized Lutheranism within the Holy Roman Empire (the German states and parts of Switzerland and Italy) with the Peace of Augsburg. His alliance with Henry VIII of England reflected another compromise of sorts, for while Henry persecuted Catholics his domestic efforts did not spread to Charles' dominions, and the theology espoused by the English sovereign was not as "radical" as that of Martin Luther. Though devoutly Catholic, Charles was no slave to the Vatican and personally wished to reform the Church in some ways. Most of his wars - both ideological and military - were essentially defensive. In 1527, his army's "sack" of Rome prevented Pope Clement VII from annulling the marriage of Henry VIII to Charles's aunt, Catherine of Aragon, with historic consequences.

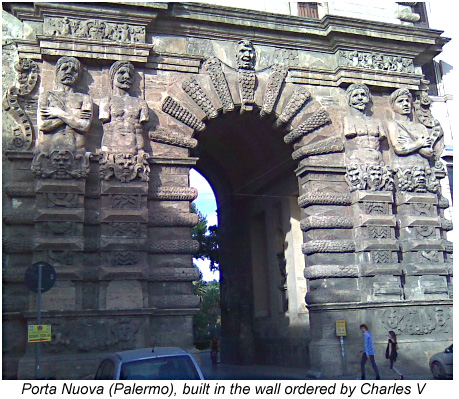

Returning from Tunis, Charles visited Sicily, arriving at Trapani on 20 August 1535, then stopping at Monreale (there the heart of another crusading king, Louis IX, was preserved) en route to Palermo, where to much fanfare he opened Parliament in the baron's hall of the Steri on 16 September. More than a century had passed since a King of Sicily had set foot here, and a medieval-style joust and other festivities marked the occasion. In Palermo Charles did not stay at the Steri Palace, the administrative center which housed his viceroy, Ferrante Gonzaga, but rather at the Palace of Baron Aiutamicristo near the "Old Fair" (now Piazza Rivoluzione). Like other homes built in the same Catalonian Gothic style in the 1490s - the Branciforte's Palazzo Abatellis comes to mind - this was a residence fit for a king or even an emperor though, unlike Palazzo Abatellis, it has been largely modified since the sixteenth century. He toured the city, visiting the cathedral, Norman Palace and other places; these probably included the Magione, until 1492 the seat of the Teutonic Order in Sicily, located near the Aiutamicristo Palace. Among other things, Charles ordered high defensive walls built to protect the important coastal cities, including Palermo, Catania, Messina, Siracusa, Trapani and others. Segments of these walls are still standing today; Palermo's Porta Nuova gate (shown here) commemorating the African victory was actually erected beginning in 1569 but almost entirely reconstructed during the following century. A near-contemporary bronze statue of the sovereign, depicted as a Roman emperor, stands down the street in Piazza Bologni. Charles remained in the capital until 14 October, when he commenced an inspection tour of the island. Travelling south and eastward, he spent a night in Polizzi Generosa, and by the 17th he was at Randazzo, near Mount Etna. He arrived at Messina on the 21st and stayed in Sicily into early 1536, visiting other areas in the eastern provinces before departing for the mainland. A few living legacies survive from Charles' reign. The world's first Jesuit school was founded at Messina under his royal charter in 1540 and evolved into that city's university, and both public libraries central Palermo are located in what used to be Jesuit monasteries (Jesuit libraries forming the basis of the original collections). The links of the (de jure) heirs of the Kingdom of Sicily to the Knights Hospitaller exist to this day, represented in close ties of cooperation in works of charity between the Constantinian Order and the Order of Malta.

To Naples and Rome, Sicily was viewed as a realm just beyond the Italian orbit, essentially a province of the united Spain, and it would remain so until the eighteenth century despite close commercial ties to Genoa and other states. Suffering various ailments, Charles abdicated his titles in 1555 and 1556, retiring to seclusion in the monastery of Yuste in Extremadura. His son, Philip, succeeded as King of Spain and Sicily. His brother, Ferdinand, succeeded as Holy Roman Emperor. He died in 1558 from a severe case of malaria and is buried in Saint Laurence monastery in the Escorial.

About the Author: Historian Luigi Mendola has written for various publications, including this one. | |

Top of Page |

Charles

V ruled half of western Europe, including Sicily, during the sixteenth century,

a pivotal period in history. He was born into the Hapsburg dynasty in 1500

and lived at a time when the

Charles

V ruled half of western Europe, including Sicily, during the sixteenth century,

a pivotal period in history. He was born into the Hapsburg dynasty in 1500

and lived at a time when the  Understandably in view of the vast and diverse dominions Charles ruled,

historical descriptions of him are colored by localized perceptions and

his influence on various movements, conflicts and trends. Protestants and

Muslims regarded him with contempt if not trepidation. To Catholics he was

either a defender of the Faith or a patron of the hated Inquisition. Spain

had been united only eight years before Charles' birth, when the Muslims

and

Understandably in view of the vast and diverse dominions Charles ruled,

historical descriptions of him are colored by localized perceptions and

his influence on various movements, conflicts and trends. Protestants and

Muslims regarded him with contempt if not trepidation. To Catholics he was

either a defender of the Faith or a patron of the hated Inquisition. Spain

had been united only eight years before Charles' birth, when the Muslims

and  In 1535, as part of his attempt to free the central Mediterranean - including

Malta and the Sicilian coasts - from the raids of Barbary pirates and the

underlying threat of Ottoman attacks, he led an army to Tunis. Charles had

already granted Malta (as a fief) to the Order of Saint John in 1530, and

the island would become the scene of great battles, but for now his victory

in Tunis altered the political landscape, even if a later raid, at Algiers

in 1541, was a failure. In fact, the Ottomans and their allies continued

to dominate the eastern Mediterranean and pirates continued to raid the

Apulian and Sicilian coasts.

In 1535, as part of his attempt to free the central Mediterranean - including

Malta and the Sicilian coasts - from the raids of Barbary pirates and the

underlying threat of Ottoman attacks, he led an army to Tunis. Charles had

already granted Malta (as a fief) to the Order of Saint John in 1530, and

the island would become the scene of great battles, but for now his victory

in Tunis altered the political landscape, even if a later raid, at Algiers

in 1541, was a failure. In fact, the Ottomans and their allies continued

to dominate the eastern Mediterranean and pirates continued to raid the

Apulian and Sicilian coasts. Charles did not alter the practice of prisoners - black and white - being

pressed into servitude, slavery being commonplace in Europe at that time

even though it had been all but abolished by the end of the reign of

Charles did not alter the practice of prisoners - black and white - being

pressed into servitude, slavery being commonplace in Europe at that time

even though it had been all but abolished by the end of the reign of