...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Vincenzo Salerno | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

This spawned the "romanesque basilica" style of ecclesiastical architecture which, truth be told, was as much Greek as it was Roman. Yet the early Romanesque was little more than an imitation of the very first temples-cum-churches. While a number of these churches can be seen in the Mediterranean world, particularly in Greece and Italy, the most imposing of all is Siracusa Cathedral, which began its life as the magnificent, golden limestone Temple of Athena during the fifth century BC (BCE), dominating the acropolis on the highest point of the island of Ortygia. The site, including an area in front of the cathedral (indicated by an outline in the pavement) where excavations were undertaken some years ago to reveal an ancient altar, was a place of worship since the earliest days of Greek Syracuse and indeed in the times of the Sikels centuries earlier. Archeologists have concluded that at least two earlier temples stood here before this one – the Sikelian structure built as early as 1100 BC and then a Greek one erected circa 600 BC. The large Doric temple was erected on orders of the tyrant Gelon following his victory against the Carthaginians at the Battle of Himera in 480 BC. The existing temple may not have reflected the city's growing importance to the extent Gelon believed it deserved. Clearly, there was an attempt to compete culturally with Athens, the "rival" city that bears Athena's name and already had a large temple dedicated to her on its acropolis – the Parthenon. In 415 BC, in connection with the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians undertook an ill-fated invasion of eastern Sicily, coming face-to-face with the temple built in seeming imitation of their own. By then Syracuse was at least as prosperous as Athens. When Plato visited in 398 BC, suggesting Sicily as his model of a utopian society, it was Syracuse he had in mind. The erudite Cicero described some of the gold and ivory bas-relief ornamentation of the temple that was stolen by Verres. The Edict of Milan of the emperor Constantine the Great granted freedom of religion to Roman citizens in AD (CE) 313. Henceforth, Christians would not be persecuted in the vast Roman Empire and various minor sects flourished as well. The sprawling Empire had been divided into eastern and western jurisdictions in 285 by Diocletian, himself no lover of Christians, but it was united – if briefly – by the "easterner" Constantine. Christianity had reached Rome with Saint Paul a few decades after the death of Jesus; it was spreading from East to West. Stopping at Syracuse en route to Rome, it was Paul who introduced the Christian faith in Sicily. Christians, of course, were not the only ones to benefit from this new freedom of religious practice; various sects, including the Jews, could practice their faith. There were Jews in Syracuse when Paul arrived, and their mikveh (ritual bath) dates to the period of the first major modifications to the temple – its evolution into a church – during the seventh century. While some Greeks and Romans undoubtedly harboured sentiments for their deities, there seemed to be comparatively few "true believers" in classical mythology by the fourth century, so some historians and theologians view Constantine's Edict as simple political pragmatism. That said, the emperor himself is thought to have embraced Christianity near the end of his life. The most striking thing about Syracuse Cathedral is that most of the original edifice, even its pavement and base set upon three steps, was left standing. The church was literally built on and around the Doric temple. Most of the columns were left standing and many are visible on the exterior walls. Inside, the wall enclosing the sella, or naos, has been preserved, though arches (visible in the last photograph shown here) were carved into it, forming a nave and two aisles. This affords us a perfect view of how Early Romanesque church architecture evolved.

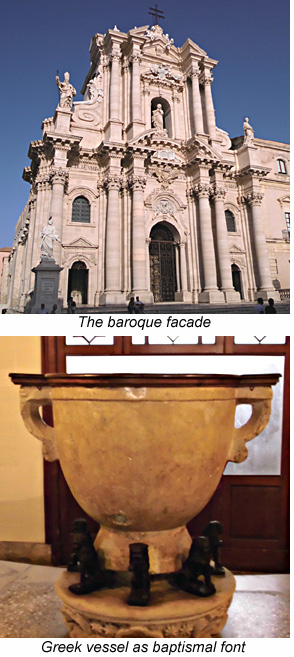

Sicily's earliest Christian tradition was Byzantine, though for a few decades following the fall of Rome to invading forces a subtle chaos prevailed and some Vandal raids led to the destruction of certain Syracusan monuments. In 535, the Byzantine general Belisarius seized control of Sicily from the Goths, making Constantinople its point of reference. Zosimo is the seventh-century "Orthodox" bishop credited with ordering construction of the cathedral, or duomo. The great church was dedicated to the Birth of the Theotokos (Mother of God). Whether this was a convenient segue from the historic veneration of Athena, the Romans' Minerva, is debated by scholars, but it seems that at least a few of the earliest Greek Christians did not readily distinguish the virgin Mary from their virgin goddess. Both gave birth to sons despite being virgins. As we've mentioned, the Parthenon of Athens was also dedicated to Athena, and like Siracusa Cathedral was dedicated to the Birth of Mary when it was used as a church. Overlooking the Ionian, Syracuse, more than most other Sicilian dioceses, looked to Constantinople, whose Patriarchs recognised it as their principal See in Sicily. Until the ninth century this was the largest and richest city on the island. In 878, the great church was sacked of its precious metal by the conquering Arabs, who converted it into a mosque. The Byzantine general George Maniakes took the city in 1038 but the Arabs - who ruled all of Sicily as several emirates - eventually returned. They were finally defeated here by the Normans led by Roger I in 1085, making Syracuse one of the last Arab strongholds of Sicily to fall to the Norman invaders. Whereas it had previously (before 878) been an "Orthodox" basilica under the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Normans appointed Latin bishops under the jurisdiction of Rome. In the event, it would be several decades before the more significant effects of the Great Schism (of 1054) were felt here. The temple's original roof was removed, and the walls were extended upward. The first wooden roof, the apses and mosaics, were added during the tenth century, modified during the Norman period. A number of modifications to the Byzantine church were effected in subsequent centuries, but most of the ornate stucco embellishments of the interior have been removed. Earthquakes damaged the church over time; one displaced the drum (cylindrical segment) of a column, a feature that is still visible today. Following the particularly destructive earthquake of 1693, the façade was rebuilt in the Baroque style, with Corinthian columns, to designs by Andrea Palma; the statues are by Ignazio Marabitti. Amazingly, it complements the structure rather than detracting from its lines and aesthetics. In a side chapel, the silver statue of Saint Lucy, the city's patron, was created by Pietro Rizzo in 1599. A relic (a piece of her arm) is also preserved here. The statue of the Madonna of the Snow (commemorating a rare snow storm in Siracusa centuries ago) dates to 1512 and is the work of Antonio Gagini. A ciborium (altar canopy) was designed by Luigi Vanvitelli, best known as the architect of the royal palace at Caserta and the engineer who stabilised the dome of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. About the Author: Palermo native Vincenzo Salerno has written biographies of several famous Sicilians, including Frederick II and Giuseppe di Lampedusa. | ||

Top of Page |

Histories

of early Christianity and the fall of the Roman Empire usually

mention the conversion of

Histories

of early Christianity and the fall of the Roman Empire usually

mention the conversion of  It would be incorrect to say that the Greek elements were "incorporated"

into the church; the structure of the church was (literally) based on the

temple. Even the stone baptismal font was originally a Greek vessel.

It would be incorrect to say that the Greek elements were "incorporated"

into the church; the structure of the church was (literally) based on the

temple. Even the stone baptismal font was originally a Greek vessel.