The Religions of Sicily

The

religions of Sicily are the faiths of the Mediterranean. Historical continuity is overpowering in such a place. Sicilian history offers

an ideal view of the development of religion in the Western World.

Coming from North or South, East or West, every civilisation

that has conquered Sicily has left its theological

influence here. In Sicily today we find Sicanian,

Greek and Roman temples. The historical traces of synagogues,

mosques and Paleo Christian churches and catacombs are more difficult

to identify. By the 6th century, Sicily was essentially Christianized,

with small Jewish communities, and in the 9th century Islam arrived.

The

religions of Sicily are the faiths of the Mediterranean. Historical continuity is overpowering in such a place. Sicilian history offers

an ideal view of the development of religion in the Western World.

Coming from North or South, East or West, every civilisation

that has conquered Sicily has left its theological

influence here. In Sicily today we find Sicanian,

Greek and Roman temples. The historical traces of synagogues,

mosques and Paleo Christian churches and catacombs are more difficult

to identify. By the 6th century, Sicily was essentially Christianized,

with small Jewish communities, and in the 9th century Islam arrived.

A Land of Faiths

A Land of Faiths

Mythology

Judaism

Islam

Christianity

Orthodoxy

Catholicism

Protestantism

A Multicultural Renaissance

A Land of Faiths

In defining the relationships of peoples

whose fundamental differences are rooted in matters of

ethnicity or religion, "tolerance" is one thing, "equality" quite another. The latter

defined Norman Sicily's "Great Experiment." It is important, from

a historical point of view, to remember that within the great Western religions there originally were no denominations per se. Jews

were not Orthodox or Conservative, Christians were not Catholic or Protestant, Muslims were not Sunni

or Shiite (though that split occurred earlier than those within Judaism and Christianity). Such terms

came into wide use later, with subsequent schisms in these religions. Historically, Judaism could be said to

be the first monotheistic faith in the Mediterranean region, supplanting mythology in many

areas. Christianity built upon Judaism, and Islam shared certain elements of both. The "Golden Age"

of multicultural (and multi-faith) Sicily lasted throughout the Norman era from around 1070 until about 1200, though

some historians extend it by a few more decades, through the reign of Frederick II, to 1250.

Following the death of that distinguished monarch, Sicily's Muslims gradually converted to Christanity, and

over time the remaining Byzantine (Greek Orthodox) clergy were replaced by Latin (Roman Catholic) bishops and priests.

The Jewish population disappeared with an infamous Spanish decree of 1492. Many Sicilian Jews

converted to Christianity, but just as many emigrated. By 1500, Sicily was Roman Catholic except for a few Albanian

Orthodox communities whose churches soon affiliated themselves with Rome.

In the words of John Julius Norwich, "Norman Sicily stood forth in Europe—and indeed in the

whole bigoted medieval world—as an example of tolerance and enlightenment, a lesson in the respect that

every man should feel for those whose blood and beliefs happen to differ from his own."

Mythology

Mythology

Persephone, Demeter, Arethusa,

Alpheus, Aphrodite, Theseus,

Daedalus, Icarus, Minos, Dionysos, Charybdis, Hades,

Hercules, Jason, Thetis, Aeolus, Polyphemus, Odysseus (Ulysses). Their names resound

in the Greek myths of antiquity, and each knew Sicily, the Greeks' New World, intimately. The Cyclopes and Vulcan (Hephaestus)

lived on volcanic Etna, the sacred mountain of Sicily's Greeks, Aeolus

and Vulcan dwelled in the islands north of Sicily, Scylla guarded the Strait of Messina, Persephone was

abducted outside Enna, Arethusa emerged at Syracuse. The Sicans, Sikels, Elymians, Phoenicians, Carthaginians

and ancient Greeks were polytheistic; they created their own Gods. Like the Elymians, Sicans and Sicels, the

Romans adopted the Greek gods as their own. Yet, unlike the Greeks, the Romans were pagans with little

faith in their own religion; Virgil's Aeneid was but an imitation of the Odyssey.

To consider classical mythology a quaint memory overlooks the fact that the very foundations of Western ethics

and democracy trace their origins from the Greece of Sophocles,

and the Sicily of Archimedes, Empedocles, Plato and Aeschylus—though there is little evidence that these

great thinkers considered mythology as anything more than a convenient cultural curiosity. When Saint Paul, who knew Greece, Sicily

and Rome, stated that the invisible must be understood by the visible, he was expressing an idea

more Greek than Hebrew. The Greeks were the first civilization to create deities in the human image,

complete with perfect human bodies and very human flaws. To the Siceliots, as the Sicilian Greeks

were known, the myths were an inspirational element of daily life in Sikelia (Sicily) rooted

in neolithic beliefs. The magnificent

Greek temples of Sicily attest to more than a people's passion; they represent the perfect union

of Humanity and Nature. After thirty centuries of progress, a combination still worth emulating. In

Malta, Europe's oldest temples were built

by the Proto-Sicanians of southeastern Sicily as early as 4,000 BC (BCE). Around three thousand years later, their

descendants built a Sicanian temple at Cefalù.

Judaism

Greek civilization created its divinities in the human image, while Hebrew culture held that humans were created in God's image. Western religious principles

are rooted in Judaic ones, but not all Semitic peoples (the Phoenicians,

for example) were Judaic in religion. The difference between God

and gods brought with it monumental implications for Mediterranean

society. As a people, the Jews were never more than a minority in

Sicily, but during the Middle Ages they comprised around eight percent of the island's

unique multicultural mosaic. There is evidence that Hebrew traders

resided in Sicily during the last centuries of Roman rule, but the first Jews in Sicily were brought

here as slaves by the Romans before the first century AD. The

successive Eastern Empire was more tolerant, and the first free Jewish

congregations grew after the time of Constantine the Great. At first,

these were communities of immigrants and descendants of former slaves, though it is clear that a number

of local people in search of faith, as opposed to mythology, converted

to Judaism. Intermarriage with Christians was not unusual in Sicily. Jewish temples were founded in

Sicily's port cities (Palermo, Messina, Syracuse) around the same time that

the first Christian churches were openly established. Sicily's jews lived more or less undisturbed

until the fifteenth century. The year 1492 signaled the unification of Spain, the European discovery

of America and the Inquisition's final banishment

of Jews from Spanish territories, including Sicily.  In Sicily, many Jews, being Sicilian in

almost every cultural sense, chose conversion (Sicily's anusim are descendants of those neofiti, similar

to the conversos and maranos of Spain), and a number of Sicilian

surnames reflect Jewish origins, or at least acknowledge a Jewish presence (Siino from Sion, Rabino from Rabbi).

Contemporary estimates of the number of Jewish Sicilians indicate that the Jewish populations of Palermo,

Siracusa (where Europe's oldest existing mikveh is preserved), Messina

and several other cities were considerable in 1492. In Palermo, the Jewish Quarter was located in the area between Piazza Ballarò and Via Roma; there is evidence

that the first merchants in the district of what is now Via dei Calderai were Jewish, and a synagogue stood near what is now Vicolo

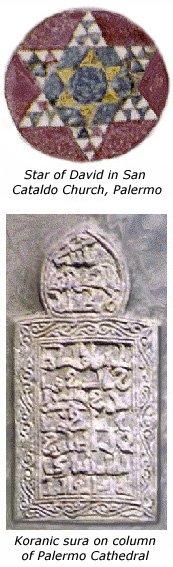

Meschita. The star or shield of David (Magen David) appears in the Palatine Chapel, San Cataldo and various other churches of

Sicily's Norman era. It remains unclear whether this was an exclusively Jewish symbol in Italy during that period, as it was

also an Arab design motif and a Christian allusion to Jesus—who was of the House of David.

In Sicily, many Jews, being Sicilian in

almost every cultural sense, chose conversion (Sicily's anusim are descendants of those neofiti, similar

to the conversos and maranos of Spain), and a number of Sicilian

surnames reflect Jewish origins, or at least acknowledge a Jewish presence (Siino from Sion, Rabino from Rabbi).

Contemporary estimates of the number of Jewish Sicilians indicate that the Jewish populations of Palermo,

Siracusa (where Europe's oldest existing mikveh is preserved), Messina

and several other cities were considerable in 1492. In Palermo, the Jewish Quarter was located in the area between Piazza Ballarò and Via Roma; there is evidence

that the first merchants in the district of what is now Via dei Calderai were Jewish, and a synagogue stood near what is now Vicolo

Meschita. The star or shield of David (Magen David) appears in the Palatine Chapel, San Cataldo and various other churches of

Sicily's Norman era. It remains unclear whether this was an exclusively Jewish symbol in Italy during that period, as it was

also an Arab design motif and a Christian allusion to Jesus—who was of the House of David.

Islam

In medieval Sicily, Islam was inextricably bound to Arab culture, though

not all the world's Muslims were Arab. The Arabs ruled Sicily

for two centuries. Most of the Muslims in Sicily were Saracens

(Moors). More precisely, many were the descendants of Sicilian

women who had wed the conquering Moors, each of whom, under Koranic law, could take

as many as four wives. Many churches and synagogues survived (though new ones could not be built), and

not every Sicilian woman chose to wed a Muslim, despite

the economic advantages implicit in such a marriage. As recently

as the thirteenth century, there were Muslims at the royal court (popes cynically referred to Frederick II, who spoke Arabic,

as a "baptized sultan"), and the Muslim towns in Sicily were essentially Arabic in every way,

not unlike the Muslim towns in Spain. There is evidence to suggest that Frederick II considered his Muslim

soldiers more loyal than many of his unruly Christian knights and barons. Certain Muslim customs (veiling, fasting)

were essentially similar to practices that had been known

among Middle Eastern Jews and Christians, and Islam's Koranic scriptures

and precepts were not completely divorced from Judeo-Christian ones. Fasting (during Ramadan),

almsgiving (zakat), pilgrimage and even Mohammed's visit by the angel Gabriel are essential elements

of Islam. The Muslims respected Jews and Christians as "people of the book." Adopting a practice

of the Muslim emirs, some of Sicily's Norman kings kept harems. In Palermo alone, there were over a hundred

mosques and Koranic schools, and hundreds of imams, when the Normans arrived. A body of evidence suggests that

Islamic law as it existed in eleventh-century Sicily influenced the early

development English common law. By the time of the Vespers War (1282), there were no professed Muslims in Sicily. Frederick II's exiled

some of them to Lucera in Apulia for armed insurrection in 1246. Sicily's

Muslims converted a number of churches to mosques, and the Normans, in turn, rebuilt some of these as churches. Like many

Jews in 1493, most of Sicily's Muslims converted to Catholicism during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a fact borne witness by artifacts

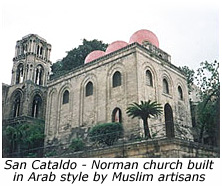

such as a New Testament written in Arabic in Palermo during this period. Arab architects designed churches in

what has come to be known as the "Norman-Arab" style. (An Arabic

inscription is visible around the high cupola of the Martorana Church in Palermo.) On the present site of

Palermo Cathedral and its square once stood Sicily's largest mosque, and before that a Paleo Christian

basilica. A number of churches in central Palermo were built on the sites of mosques. In keeping with this

peculiar architectural tradition, the Archdiocese of Palermo some years ago gave a former church to the

city's growing Muslim community for use as a mosque. Veiled women

are an increasingly common sight in the city, where a pillar of the portico of Palermo Cathedral is

inscribed with the enduring Arabic words of the first sura of the Koran: God is Allah and Muhammed is His Prophet.

Christianity

Christianity

There was already a small Christian community in

Syracuse when Saint Paul preached there, though in his time the

Christians were still a covert sect persecuted by the Empire. A number of Greek and Roman temples were eventually converted into

churches; Syracuse Cathedral, formerly the

Temple of Athena, is the most magnificent example still standing. The essence of the historical Church in Sicily is rooted

in the Byzantine East, in the tradition which is today preserved in the Orthodox Church. It began in Palestine. The Normans

arrived just a few years after the Great Schism (1054), in which

the Patriarch of Rome (the Pope) separated from communion with the other patriarchs

of the Church. The reasons for this were social as well as theological, but for most of Sicily's Christians the effect was not felt immediately.

Orthodoxy

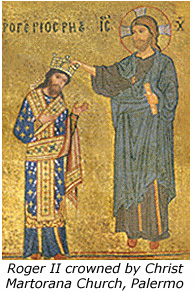

The Norman kings, whose Italian conquests were sanctioned

by the Popes of Rome, are generally viewed, theologically speaking, as "Latinizers." Yet,

during the reign of Roger I the Archimandrite Neilos

Doxopatrios authored a book, published in Sicily,

refuting the supremacy of the Roman Pontiff. The cathedral of Cefalù

is distinctly Romanesque, with certain Gothic elements, while

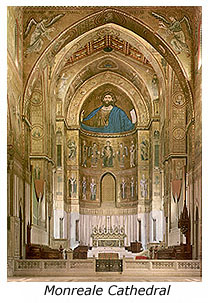

the cathedral of Monreale, and the churches of the Martorana (Palermo)

and the Annunciation (Messina) are more similar to what one might

encounter in Greece. Despite eclectic styles, all were constructed during the same

period. The Martorana, in fact, was built specifically as an Orthodox place of worship.

The Schism's theological implications

became evident over time, as the Western

Church itself evolved. Superficially, statues replaced icons,

and the liturgy was altered. The mosaic icons in the Martorana,

the Palatine Chapel, Monreale Abbey and (to a lesser extent) Cefalù

Cathedral reflect a Byzantine heritage. They also indicate an

Orthodox presence for some time after the arrival of the Normans.

This was most evident in Sicily, but even the Normans' Royal Chapel

in the Tower of London is more typical of Orthodox churches than

it is of subsequent (Catholic) ones based on the Romanesque and

Gothic models. In social matters, the Schism paved the way for

a more Italianate (and Papal) orientation which, in retrospect, brought Sicily's

unique medieval interfaith experiment to an early demise. Yet Byzantine monasteries in northeastern Sicily's

scenic Nebrodi Mountains continued to thrive into the fourteenth century.

There came a new influx of Orthodox Christians into southern

Italy with the Albanian immigration of the 15th century. These

parishes soon became "Uniate"—being in union with Rome. Today, their liturgy

and customs are Orthodox but in fact they are Byzantine Rite parishes of the Catholic Church.

Catholicism

Sicily's early kings enjoyed the title and function of Apostolic (papal) Legate, though as a fundamental

principle of law the Sicilian Crown was granted not by any Pope but emanated from God Himself.

Ecclesiastical Sicily gravitated toward Rome very slowly indeed; occasional excommunication was something the

Norman and Swabian kings took in stride. The new dioceses founded in Sicily during the Norman period, in places

like Monreale and Patti, were under the canonical jurisdiction of Rome and used the Gallican Rite. Some of the

new bishops were Normans; Bishop Walter "of the Mill" (his name actually a misnomer based on a

mistranslation) was a cousin of the royal Hautevilles. Sicily's Eastern tradition didn't vanish immediately

but, like the Normans themselves, it was all but forgotten within a few centuries. Byzantine Venice, Bari and Ravenna

suffered the same fate.

How was Catholicism different from Orthodoxy? There were theological matters, such as the controversial

"filoque" passage of the Creed, while the ecclesiastical primacy of one man (the Pope)

also distinguished Catholics from their Orthodox brethren, whose patriarchal leadership was

collegial. The Crusades were a

Catholic phenomenon. Latin's replacement of Greek as the liturgical language represented perhaps the least significant alteration.

Liturgy itself changed radically from that which existed in Norman times, and with it the role of the clergy.

Even the churches were different. The icon screen was omitted, and statues of saints (as opposed to the icons

or simple bas-reliefs of earlier times) became increasingly commonplace in Western churches, where the Gothic,

the Baroque and the Italian Romanesque supplanted the austere ecclesiastical architecture of the East. Over

time, the doctrines of Original Sin and the Immaculate Conception, Purgatory and indulgences, and other Latin

ideas rooted in late-medieval Western philosophy further distinguished Catholicism. One of the greatest differences

between East and West had little to do with theology as such, though it was rooted in Rationalism. Under the auspices

of the Catholic Church, the Renaissance, in all its glory, fostered a fundamental change in creative and philosophical

thought (Humanism), and the true end of the Middle Ages. But yet another schism, the Reformation, would challenge some of its ideas.

How was Catholicism different from Orthodoxy? There were theological matters, such as the controversial

"filoque" passage of the Creed, while the ecclesiastical primacy of one man (the Pope)

also distinguished Catholics from their Orthodox brethren, whose patriarchal leadership was

collegial. The Crusades were a

Catholic phenomenon. Latin's replacement of Greek as the liturgical language represented perhaps the least significant alteration.

Liturgy itself changed radically from that which existed in Norman times, and with it the role of the clergy.

Even the churches were different. The icon screen was omitted, and statues of saints (as opposed to the icons

or simple bas-reliefs of earlier times) became increasingly commonplace in Western churches, where the Gothic,

the Baroque and the Italian Romanesque supplanted the austere ecclesiastical architecture of the East. Over

time, the doctrines of Original Sin and the Immaculate Conception, Purgatory and indulgences, and other Latin

ideas rooted in late-medieval Western philosophy further distinguished Catholicism. One of the greatest differences

between East and West had little to do with theology as such, though it was rooted in Rationalism. Under the auspices

of the Catholic Church, the Renaissance, in all its glory, fostered a fundamental change in creative and philosophical

thought (Humanism), and the true end of the Middle Ages. But yet another schism, the Reformation, would challenge some of its ideas.

Protestantism

The Waldensian Church never had a strong presence in Sicily. A

Waldensian parish was established in Palermo after the Unification

(1860), their church having been more widespread in Piedmont,

the Savoys' realm. The Anglican Church was introduced early in

the 19th century with the arrival of several English mercantile families.

In Sicily, it is still represented in the "High Church"

tradition of the Church of England. When General George Patton

arrived in Palermo in 1943, it was at Holy Cross Anglican Church

(on Via Roma) that he worshipped, where he dedicated a plaque to

commemorate the American soldiers killed during Operation Husky,

the Sicilian campaign. Waldensians and Anglicans are Protestants in the Reform tradition.

A Multicultural Renaissance

The twentieth

century saw the arrival of other faiths in Sicily, and an increasing number of atheists. There has been a minor revival

of Eastern Orthodoxy, a strong Evangelical movement, and an increasing

number of Buddhists. Several mosques have been established by

North African immigrants. After nine centuries, Sicily has reclaimed

something of her multicultural religious heritage. It's one aspect

of twenty-first century Sicily that King Roger II would certainly recognize.